Fig.1 Marcel Duchamp, Encore à cet Astre (Once More to This Star), 1911

It has been some twenty-five years since Lawrence D. Steefel Jr.'s analysis of Marcel Duchamp's 1911 drawing Encore à cet Astre (Once More to This Star) (Fig. 1) was published by Art Journal.(1) Despite Steefel's suggestion that Duchamp's minor works, primarily his sketches and drawings, be allotted a greater degree of recognition for what they reveal about Duchamp's creative process as a whole, Encore is still generally accorded little significance beyond its being a study for the Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Fig. 2).(2) I felt compelled to write about this particular drawing because I strongly agree that Encore has-and continues to be-relegated to a minor status as little more than a precedent for the Nude…No. 2. While Encore is indeed a small sketch, it would be, in this case, presumptuous to judge significance merely according to appearances.

Fig. 2 Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1911

It is crucial to remember that the end of 1911 was a pivotal period in Duchamp's career. In the last two months of 1911, Duchamp produced several of his most well known paintings, including Portrait of Chess Players, Sad Young Man on a Train, and the major study for the Nude… No. 2, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1. All of the aforementioned paintings have been in some way related to Encore (some more directly than others), yet these relationships have been far from exhausted. In this article, I intend to more fully situate Encore within this period of Duchamp's life and art by examining Encore in relation to contemporaneous works, as well as introducing heretofore unaddressed precedents and possible inspirations for this drawing. My motivation for writing this essay was not to "explain" this sketch or to unearth its "meaning," for I wouldn't propose to do that with any of Duchamp's works, especially one as enigmatic as Encore. Rather, I would like to suggest a number of possible influences, inspirations, and intentions based on Duchamp's own work of the time and the ideas of more recent scholars.

.jpg)

Fig.3 Charles Willson Peale, Staircase Group: Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay, 1795,

Philadelphia Museum of Art

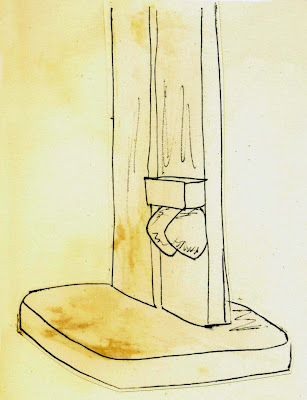

Encore consists of three main parts.(3) In the center, a heavily-shaded head(4) rests on a hand or fist, with only a thin line describing a right shoulder and bent right arm. To the left of the head is what appears to be a female figure from the waist down; above the waist is a sectioned cylindrical element topped with swirling lines reminiscent of hair. To the right of the head is what has come to be the most important element, a goateed male figure ascending a staircase.(5) The figure's head is drastically turned in order to peer at a grid to the right or behind the figure, which Steefel described as a "barred window." As I agree with Steefel's interpretation of the "female" figure as a "sex object,"(6) I will concentrate primarily on the other two elements of the drawing, after which I will suggest a reading that integrates all three elements.

Joseph Masheck noted that there is an uncanny resemblance between the ascending figure in Encore and the ascending figure in Charles Willson Peale's hyperrealistic Staircase Group: Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay (1795) (Fig. 3), which is, like Duchamp's drawing, in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.(7) While Masheck made a case for Duchamp possibly having seen a reproduction of the Peale painting in Paris (Encore preceded Duchamp's first visit to the United States by more than three years), an association between the two images, though enticing, remains dubious.(8) A more practical-and arguably more similar-precedent for the ascending figure is found in a painting with which Duchamp was undoubtedly familiar, the silhouetted figure of Don José Nieto in the background of Velásquez's Las Meninas (1656) (Figs. 4 and 5).

.jpg)

Fig.4 Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas, 1656, Museo del Prado

.jpg)

Fig.5 Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas, detail

Though the resemblance between the two figures is far from exact, the figures' postures, particularly the positioning of the legs, head, and right arm (if the roughly horizontal line extending from the above the hip of the ascending figure to the central head's left eye does indeed describe an arm) are similar enough to merit a comparison. Even the coffered door to Nieto's left has a gridded appearance akin to the grid to the right of the figure in Encore, albeit on the opposite side. In Encore, the artist's perspective is a bit different, with the stairs in three-quarter view and the head in full profile; a comparison with Las Meninas shows that the ascending figure is drawn from virtually the same angle that Velásquez would have seen Nieto in the mirror (Velásquez would not have seen Nieto as we do in the painting because the artist is off to the side.) Could this figure that so intrigued Michel Foucault have had a similar affect on Duchamp?

.jpg)

Fig. 6 Robert Fludd, Utriusque Cosmi, vol. 2, Oppenheim, 1619

It is not enough to simply claim the figure in the Velásquez painting as a model for the ascending figure without an explanation. The figure of Nieto in Las Meninas has long fascinated scholars because of his transitional status; he inhabits a space that is both invisible to the viewer yet implied by his presence. Even more important to Duchamp, I believe, is the ambiguity of his presence, due to the fact he is neither entering nor exiting the room, but, in Foucault's words, "coming in and going out at the same time, like a pendulum caught at the bottom of its swing."(9) Like Nieto, the figure in Encore is positioned in such a way that he appears to be traveling upward, yet the severe turn of his head and downward gaze imply an impeding reversal of motion, or at least the potential for a reversal of motion, rendering the figure, like the Sad Young Man on a Train and Nude Descending a Staircase, simultaneously static and dynamic.

.jpg)

Fig.7 Ramon Lull, De nova logica, 1512

But why a staircase, and what is its relationship to the title? As Siegfried Giedion indicated, the diagonal planes of a staircase leading the eye upward led to the stair becoming "the symbol of movement."(10) The general interpretation that the figure is ascending toward the sun/star of the poem is made less feasible by the figure's backward and downward glance. Moreover, as Jerrold Seigel noted, "the 'to' in Laforgue's title was a preposition of address, not of physical movement."(11) Regardless, those who champion readings of Duchamp's works that embrace his heavily debated involvement with the history and theory of alchemy(12) may support the reading of the figure ascending toward the sun/star, as ladders and staircases (which have a closely-tied history and symbolism) are legion in alchemical images and texts. Images of ladders and staircases leading to a star, the sun, or a heavenly/celestial realm (Figs. 6 and 7) support the notion that "the vertical…has always been considered the sacred dimension of space."(13) That the direction of the figure's movement remains ambiguous does not necessarily contradict the alchemical interpretation, as the hermetic theologian and neoplatonist Cardinal Nikolaus of Cusa (known as Cusanus) indicated: "Ascending and descending…are one and the same. The 'art of conjecture' lies in connecting the two with a keen intelligence."(14) Another possibility of interpretation takes into account Duchamp's predilection for wordplay, being that "astre" is an anagram for "stare" (which the figure on the right certainly does), which is a homonym for "stair."

.jpg)

Fig.8 Grid in perspective

But at or through what is the figure staring? The density of the vertical lines and the converging horizontal lines are certainly meant to convey deep foreshortening (Fig. 8), so one may deduce that the incomplete, hastily drawn grid contains squares and not rectangles. The grid can represent innumerable possibilities: Dürer's device for drawing perspective (Fig. 9), the checkered mosaic tiles of the Temple of Solomon, generally found in Masonic lodges, and the magic square, to name a few.

.jpg)

Fig.9 Albrecht Dürer, Draughtsman Drawing a Recumbent Woman, 1525

A possibility that I would like to pursue, however, is that the grid represents a chessboard, due to the fact that the grid contains eight squares at its widest point, the same number of squares on a chessboard. The fact that the grid is vertical rather than horizontal should come as no surprise, since chessboards have been displayed vertically in order to study problems since the Middle Ages (Figs. 10 and 11). Duchamp himself had numerous chessboards displayed vertically in his studio, as recorded in several photographs (Figs. 12 and 13).

.jpg)

Fig.10 Illumination from the Manuscript of Alfonso the Wise, 1283, Escorial Library

.jpg)

Fig. 11 Woodcut of a King and a Bishop playing chess, illustrated in William Caxton,

Game and Playe of the Chesse,(London: Elliot Stock, 1883)

Fig.12 Photograph of Duchamp's Studio, 1917-18

Fig. 13 Photograph of Marcel Duchamp taken by Denise Bellon, 1938

Moreover, several of his studies for Portrait of Chess Players show the chessboard not only horizontally, but scattered throughout the composition, in some cases above and behind the heads of the players (Figs. 14 and 15). If the figure on the right is examining a chessboard, it may lead to an understanding of the role of the central "head."

Fig.14 Marcel Duchamp, Study for Portrait of Chess Players, 1911

Fig.15 Marcel Duchamp, For a Game of Chess, 1911

The position of the central head, with the head resting on the hand or fist, is a posture inextricably linked with chess players, as it is seen in myriad representations of the subject (Figs. 16 and 17). Duchamp used this iconic posture for the figure of Jacques Villon in nearly all the studies for Portrait of Chess Players and in the final oil painting (Fig. 18).

.jpg)

Fig.16 William Henry Fox Talbot, Chess Players, 1840

Fig.17 Honore Daumier, The Chess Players, 1868,Musée du Petit Palais

Fig.18 Marcel Duchamp, Portrait of Chess Players, 1911

Duchamp himself appears in this manner on several occasions, as seen in a photograph used for a window display devoted to Duchamp at the bookshop La Hune in Paris in 1946 (Fig. 19), and in the sculpture Marcel Duchamp Cast Alive (1967) (Fig. 20), executed by Alfred Wolkenberg, which bears an eerie resemblance to the head in Encore. There are certainly practical explanations for the intimate communion shared by the game and this posture; chess games can go on for extended periods of time, during which the neck grows tired and requires additional support. However, in several instances, the hand at the chin appears to support the figure mentally rather than physically.

Fig.19 Window Display, La Hune Bookshop, Paris, 1946

Fig.20 Marcel Duchamp and Alfred Wolkenberg, Marcel Duchamp Cast Alive, 1967

No doubt the most famous, reproduced, and parodied image of thought of the twentieth century is Rodin's Thinker (Fig. 21), who, rapt in his all-consuming contemplation, is the icon for the workings of the human mind. Centuries earlier, Michelangelo's depiction of Lorenzo de' Medici at the latter's tomb in Florence (Fig. 22), which has often been cited as a model for Rodin's allegory, was dubbed "Il Penseroso" due to the contrast of his downcast eyes and inward expression with the more active, outward thrust of the sculpture of his brother Giuliano. The fact that both chess players and "thinkers" share the same conventions for representation is far from coincidental, as chess is considered among the most difficult and intellectual of pursuits. Duchamp often stated that art should be more like chess, which is "completely in one's gray matter,"(15) or, in Hubert Damisch's words, "cosa mentale."(16) His desire for art to become "an intellectual expression" was ultimately realized with the Readymades and the Large Glass,(17) but signs of this desire are visible as early as his studies for the Portrait of Chess Players.

There is, however, another association to be made with the posture of the central head, one which may be linked to another important painting by Duchamp produced at or near the same time as Encore. For centuries, the propped-up head had an association with another type of thinker, the melancholic. Melancholy, an affliction thought by medieval scientists to have been brought on by an imbalance of bodily humors and the positions of the planets, was exalted during the Renaissance by humanists as a sign of genius.(18)

.jpg)

Fig. 21 Auguste Rodin, The Thinker,1879-89

.jpg)

Fig. 22 Michelangelo,Lorenzo de' Medici, Medici Chapel, Florence

Fig. 23 Raphael, School of Athens, 1510-11, detail

These humanists championed Saturn, who "was discovered in a new and personal sense by the intellectual elite, who were indeed beginning to consider their melancholy a jealously guarded privilege, as they became aware both of the sublimity of Saturn's intellectual gifts and the dangers of his ambivalence."(19) Among the more famous portrayals of the saturnine artist is Raphael's depiction of Michelangelo (Fig. 23), a self-proclaimed melancholic, in his School of Athens (1510-11).(20) Certainly the most famous image of melancholy (and one of the most analyzed images in the history of art) is Dürer's engraving Melencolia I (Fig. 24), interpreted by Erwin Panofsky as a "spiritual self-portrait,"(21) through which Dürer represented "the melancholic artist, both cursed and blessed with a wider range of knowledge and a glimpse into the realm of metaphysical insight, [who] is painfully aware of the discrepancy between the necessary physical concerns of art and the higher metaphysical understanding that is desired."(22)

Fig.24 Albrecht Dürer,Melencolia I, 1514

Melencolia I has already been linked with Duchamp's work by Maurizio Calvesi, who indicated that both artists had a shared interest in alchemical imagery.(23) A close comparison of the melancholic angel in Dürer's engraving and the central head in Encore reveals that the two figures share two conventions that Raymond Klibansky, Fritz Saxl, and Panofsky called "the clenched fist and the black face,"(24) meaning that both heads are propped up by a fist and the faces are heavily shaded. These conventions, which were originally physiognomic symptoms of a medical affliction, were appropriated by humanists to signify a mental rather than a physical condition.(25) In addition to Dürer's famous engraving, Duchamp could have seen these conventions used by another artist for whom his admiration is well documented, Odilon Redon,(26) whose Penseroso (1874) (Fig. 25) and Angel in Chains (1875) (Fig. 26) owe a debt to Michelangelo and Dürer, respectively.(27)

.jpg)

Fig. 25 Odilon Redon, Renseroso, 1874

If the central head of Encore does indeed reflect the conventions of the melancholic artist, does this possibility have any bearing on the title of the Sad Young Man on a Train (Fig. 27), painted shortly after Encore was produced? While Duchamp insisted that the young man's "sadness" was introduced merely for the purposes of alliteration ("triste" and "train"), Seigel pointed out that the painting's original title, "Pauvre Jeune Homme M.," maintained the same mood minus the alliteration.(28)

Fig. 26 Odilon Redon, Angel in Chains, 1875, The Woodner Family Collection

Moreover, the original title was, like Encore, taken from Jules Laforgue, leading to the possibility that Encore may in some way be a study for the Sad Young Man. Steefel's descriptions of Duchamp in late 1911 as "fiercely intellectual," "private and eccentric under a cloak of pervasive 'Hamletism' and desultory ennui," and subject to "an inhibiting malaise of spirit"(29) support the notion that the "sad young man," who Duchamp clearly indicated is a self-portrait, may in fact be a self-representation as the melancholic artist.

As I stated at the beginning of this essay, I find Steefel's reading of the "female" figure at the left as a "sex object" very persuasive, and her mechanomorphic sexuality is likely an anticipation of Duchamp's other paintings involving "the erratic mechanism of human desire."(30) It is tempting to try to understand Encore, one of Duchamp's many tripartite compositions, as a single idea, an integrated image in which the three elements have some common denominator. Encore seems to be the very definition of Foucault's concept of the heteroclite, of things "'laid', 'placed', 'arranged' in sites so very different from one another that it is impossible to find a place of residence for them, to define a common locus beneath them all."(32) As it is highly unlikely that the three elements were conceived and intended to be seen independently, an integrated reading appears to be in order.

From the various analyses of the elements of Encore I have endeavored to support, a pattern may be inferred: the staircase, a symbol most commonly associated with spiritual concerns; the chess player or melancholic, both of whom are linked to the intellect; and the mechanical/female "sex object," or, like the later coffee and chocolate grinders, a "sex machine." Taken together, the spirit, the intellect, and the carnal are all forms of desire-the desire for salvation, the desire for the acquisition of knowledge or creative growth, and lust. Desire, specifically unfulfilled desire, became one of the critical operators in Duchamp's work, from his distanced disrobing of Dulcinea to the perpetually unconsummated desires of the bride and bachelors.(33) For indeed, by assiduously attempting to locate any logical continuity to conjoin the three figures in Encore, we find ourselves more intimately acquainted with the notion of frustrated desire.

Fig. 27 Marcel Duchamp, Sad Young Man on a Train, 1911

Text by Bradley Bailey

(For Dario Gamboni)

Notes

1. Lawrence D. Steefel, Jr. "Marcel Duchamp's Encore à cet Astre: A New Look," Art Journal 36, no.1

(1976): 23-30. At the conclusion of Steefel's article, an English translation of Laforgue's poem is included under

the title "Another for the Sun," which Steefel indicated came from a translation by William Jay Smith in his

Selected Writings of Jules Laforgue. Ron Padgett translated the title as "Again to this Star," Pierre Cabanne,

Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Da Capo, 1987) 46. Another translation of the

title, "Once More to this Star," is more commonly used in reference to the Duchamp drawing.

2. "Widely recognized as a 'first step' towards the evolution of the famous Nude Descending a

Staircase, painted a month or so after the drawing Encore was completed, the drawing itself has been

disregarded as a work of art in its own right and, more surprisingly, has been persistently misread simply as

an image by all previous commentators, including Duchamp himself referring to what it presumably is 'about.'"

Steefel, 23.

3. For a more detailed ekphrasis, see Steefel, 24-25.

4. Steefel called this element of the drawing a "mask," possibly because it lacks ears and hair. However,

the figure on the right lacks any discernible ears or hair, yet there is no mention of this figure being masked.

To avoid inconsistency, I will simply refer to this element as a head.

5. Steefel indicated that it is a spiral staircase (25), which is certainly the case with Duchamp's later

descending figures. Unless the scribbled out lines above the figure's head, which Steefel claimed may be

"a possible vault of the lower staircase" (26), are the spiraling continuation of the staircase, I see no evidence that

this particular staircase is helical.

6. Steefel, 25.

7. Joseph Masheck, ed., Marcel Duchamp in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1975) 7-8.

8. Schwarz stated that "[Duchamp] could not possibly have seen the Peale before completing this study." Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 3rd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Delano Greenidge, 1997) 555.

9. Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (New York: Vintage, 1994) 11.

10. Siegfried Giedion, The Eternal Present (New York: Pantheon, 1964) qtd. in John Templer, The Staircase: History and Theories (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1992).

11. Jerrold Seigel, The Private Worlds of Marcel Duchamp (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1995) 38.

12. See Arturo Schwarz, "The Alchemist Stripped Bare in the Bachelor, Even," in Anne d'Harnoncourt

and Kynaston McShine, Marcel Duchamp (New York: Museum of Modern Art; Philadelphia:

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973) 81-98; and Maurizio Calvesi, Duchamp invisible (Rome: Officina edizioni,

1975).

13. Christian Norberg-Schulz, Existence, Space and Architecture (New York: Praeger, 1978) qtd.; in

Templer, 34.

14. Alexander Roob, The Hermetic Museum: Alchemy and Mysticism (New York: Taschen, 1997) 282.

15. Schwarz, Complete Works, vol. 1, 73.

16. Hubert Damisch, "The Duchamp Defense," trans. Rosalind Krauss, October 10 (Fall 1979): 5-28.

17. Schwarz, Complete Works, vol. 1, 73.

18. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy (New York: Basic Books,

1964) 241-254.

19. Ibid., 251. For more about the melancholic temperment as it pertains to artists, see Rudolph and Margot Wittkower, Born Under Saturn (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1963).

20. Klibansky et al, 232 and Wittkower, fig. 21.

21. Erwin Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1955)

171.

22. Linda Hults, The Print in the Western World (Madison, WI.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996)

95.

23. Maurizio Calvesi, "A noir, Melencolia I," Storia dell'Arte 1-2 (1969): 37-96. Duchamp invisible; Arte e

alchimia (Florence: Giunti, 1986). See also Giuseppina Restivo, "The Iconic Core of Beckett's Endgame,"

in Marius Buning, Matthijs Engelberts, and Sjef Houppermans, Samuel Beckett: Crossroads and Borderlines:

L'œuvre Carrefour/L'œuvre Limite (Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi, 1997) 118-124.

24. Klibansky et al, 290.

25. Ibid., 320.

26. Seigel, 50.

27. Douglas W. Druick, ed. Odilon Redon: Prince of Dreams, 1840-1916 (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago;

New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994) 79-80, 84.

28. Seigel, 59.

29. Steefel, 23.

30. d'Harnoncourt and McShine, 256.

31. Young Man and Girl in Spring (1911), 2 Personages and a Car (1912), The King and Queen

Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912), and The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors (1912) are but a few examples.

Both Robert Lebel and Harriet and Sidney Janis have noted Duchamp's penchant for the number

three in his work. Schwarz, Complete Works, vol. 1, 128.

32. Foucault, xvii-xviii.

33. Seigel, 41, 94-97 and Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973) 39, 42, 44.

Source : www.toutfait.com

The Marcel Duchamp online Journal, issue 4, Jan.02

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)