Long

respected as something of a Mexican national treasure, the

German-born, naturalized-Mexican artist Mathias Goeritz is at the

time of the writing of this text the recipient of significant

international attention, thanks largely to his retrospective, “The

Return of the Snake,” at the Reina Sofia, which ran from November

2014 to April 2015 in Madrid. This traveling retrospective, which

just opened at the Palacio de Iturbide in Mexico City and will

thereafter travel to the Museo Amparo in Puebla, Mexico, offers a

unique and valuable opportunity to appreciate and evaluate the

overall output and ongoing impact of this complex, highly

controversial and protean figure, especially within the context of

postwar modernities. Perhaps more importantly, it offers the

opportunity to not only consider his work then and now, but also the

similarities between his epoch and our current one, as well as some

of the issues at stake in each moment.

Mathias

Goeritz, Museo El Eco (1952-53

Probably

most famous for inventing the term “emotional architecture”

(which is in fact, something of an architectural hapax legomenon),

Goeritz was born in Danzig, Germany (today Gdansk, Poland) in 1915,

and after a stint in both North Africa and then Spain, moved to

Guadalajara in 1949 and then to Mexico City, where he lived until his

death in 1990. An art historian, sculptor, and painter, he came up

with the term and corresponding manifesto “emotional architecture”

at the inauguration of the Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City

in 1953, which he designed (also the city’s first museum of modern

art). Devoid of so much as a single right angle, this singular piece

of architecture, which resembles a cross between a set from

Expressionist German cinema and a De Chirico painting, was conceived

in response to what Goeritz saw as the stultifying effects of the

rationalization of international style in modern architecture. Having

arrived in a post-revolutionary, heavily pro-nationalist atmosphere

steeped in the social realism of the muralists, Goeritz’s many

innovations, ranging from non-figurative or abstract sculpture to

monochrome painting, represented a kind of taboo cosmopolitanism, and

for some figures even represented a damnable complicity with

capitalist imperialism. As such, he and his work were severely

criticized and in some cases rejected, and he was ultimately

undermined (for instance, in a well-known incident of public

opposition, when Goeritz was named museógrafo

at the Universidad Nacional de Mexico in 1954, David Alfaro Siqueiros

and Diego Rivera published a letter of protest in the newspaper

Excelsior demanding the repeal of his position, which was actually

met with success).

As

such, it is difficult to call them monochromes in the sense that is

now generally associated with the monochrome, which is more about its

own materiality and color than a means to an end, which in the

Mensajes is light and spirituality, and even more to the point, god

(In hopes of underlining the work’s relationship with light,

Goeritz created dramatic strategies of exhibition in which

the Mensajes

were, for example, lit only by candlelight). According to Garza

Usabiaga, Goeritz was critical of the so-called realism of some

currents such as the Nouveaux Réalistes in France, in the sense that

their work merely replicated and perpetuated the chaos of everyday

life. “To counter this type of practices [sic], Goeritz championed

an art of stable referents, and as he said, God was the most stable

of all. […] Light is a perfect way to represent this religious

referent. The monochrome works in the same way. As the zero-degree of

representation, it is a symbol of ‘the whole and of

nothing.’(2) Almost ironically, once abstraction and the

monochrome later became accepted in Mexico – and largely thanks to

his efforts – Goeritz himself became critical of their apparent

status as mere merchandise.

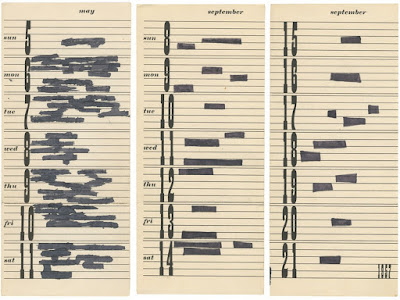

Mathias

Goeritz, Mensaje,

circa 1959, goldleaf on wood, 53 1/8 x 48 in / 135 x 122

It

is for these reasons that when all is said and done – and this is

admittedly a radically ham-fisted simplification of a very complex

historical conflict – one can finally recognize similarities of

agendas between the muralists and Goeritz. In the truly dogmatic

spirit of the European avant-garde, and whatever their relationship

to the production of objects might have been, they both essentially

saw art as a means to an end, which was as pedagogical as it was

ideological, and which zealously promoted, or rather proselytized a

“correct” way of life. They respectively fought for a hegemonic

position, as it was natural for an vanguard artist at the time, at

the natural exclusion and ideal suppression of all the others.

Therein lies what is possibly the greatest “evil” of not only

modernity, but even contemporary art (unfortunately, this intolerant,

anti-pluralistic, winner-take-all mentality is still very entrenched

in certain parts of contemporary practice). Artistic manifesto

positions of the time can be seen from our times as essentially

retrograde and conspicuously reminiscent of religious fundamentalism,

as they always sought to establish an aesthetic orthodoxy, which

itself inevitably led to conservatism (we know now that orthodoxy

must always be protected from the unorthodox and protected from

heterodoxy). But here’s the good news: The conservative and

retrogressive always loses, historically speaking. For better

or for worse, this is an immutable law of (art) history, and if there

is any lost cause in the history of art, it is the repression or

retardation of change – which, it just so happens is often

enforced by either the academy or totalitarian states. Of

course, for any art professional who is truly committed to what they

are doing, the hegemonic temptation, retrograde in of itself, is

always there, but this is the temptation that must be resisted.

Text

by Chris Sharp

Notes:

(1) Mathias

Goeritz, La Arquitectura Emocional: Una Revisión Crítica

(1952-1968), published by Conaculta, INBA, and la Universidad

Autónoma de Nuevo León.

Ibid,

p. 385