He truly loved the purple sun, descending from the hills,

The ways through the woods, the singing blackbird

And the joys of green.

Sombre was his dwelling in the shadows of the tree

And his face undefiled.

God, a tender flame, spoke to his heart:

Oh son of man!

Silently his step turned to the city in the evening;

A mysterious complaint fell from his lips:

“I shall become a horseman.”

But bush and beast did follow his ways

To the pale people’s house and garden at dusk,

And his murderer sought after him.

Spring and summer and – oh so beautiful – the fall

Of the righteous. His silent steps

Passed by the dark rooms of the dreamers.

At night he and his star dwelled alone.

He saw the snow fall on bare branches

And in the murky doorway the assassin’s shadow.

Silvern sank the unborne’s head.

Georg Trakl

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Kaspar Hauser's Song

Saturday, September 29, 2007

Design and Hierarchy

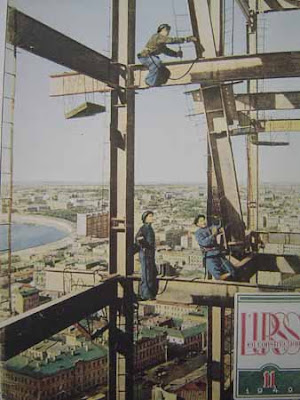

The notion of power can have a cosmological content, something that functions as a principle of order and inhabit the ordinary practices of life. If all this seems convincing I can easily explain what is the structure that defines the foundation of ideologies and so on. Normally a studio based production of works reflects these power relations, not necessarily among humans but between objects and subjects that offer the gesture of hierarchical discourse to the human environment. Objects then become cultural representations of values which unconsciously define ways of belief. Here i display some stills from my craft experience, and especially some details(not the whole installation) from some recent stuff that i will normally show during the next couple of months.

Be ready to Defend October

Labels:

archive,

my stuff,

sculpture,

Social History

Thursday, September 27, 2007

A Psychic Vacuum

Mike Nelson has been working day and night at the abandoned Essex Street Market to create what he calls A Psychic Vacuum. The space has been closed off for 13 years and is now home to Nelson's first major New York exhibition. The 6,500 sq foot installation is a labyrinth of 10 rooms that create a fictional world with inspiration from the world outside its doors.

Upon the opening of the space last week we asked the artist a few questions about the experience and stopped by to get a sneak peak. The exhibition, located at 117 Delancey Street, runs through October 28th (Friday through Sunday, noon-6pm

How did the Essex Street Market become the site for your first major U.S.

installation?

Creative Time had been looking for the right space for over a year and located that site. It was an interesting building that was unknown to most people and therefore ideal to create a new fictional environment.

The installation is partially inspired by the building's history and the surrounding neighborhood -- can you expand upon how?

The neighborhood was of interest as it's a place in transition and has a history of a variety of immigrants being moved through. Specifically the abundance of tattoo parlors, clairvoyant storefronts, and biker shops, as well as the building's own history including the Chinese restaurant at the entrance and meat freezer rooms all inspired aspects of the installation.

What did you learn while researching the building?

Well there were garters, scarves, underwear and mattresses upstairs, and nocturnal life all around, so you can draw your own conclusions. The Chinese restaurant, the first room of the installation, was left with dirty dishes, oil spilled, even a $2 tip in one of the envelopes – it looks like it was vacated quite urgently.

What sort of remnants from the building did you use?

There was a map of the U.S. hanging on the wall upstairs that was torn in half and really striking so we moved that to the installation downstairs. I often use found objects in my installations, and this image also became part of the announcement.

The peeling paint is courtesy of the space, and we used one of the meat freezer rooms in the show in which you can catch a whiff of its original use. The windows in the last room provide beautiful light that shifts throughout the day creating different experiences with the work.

Most material was found outside the building including Materials for the Arts archived prints of tattoos and old photo prints, and finds from flea markets in upstate NY.

The space is also inspired by different literary authors, who did you garner inspiration from and how did it effect the work?

Lovecraft, Borroughs, Bradbury – ideas and inspirations come from all over and subtly inspire visual directions in the work.

Which New Yorker do you most admire?

Moments working late, alone in the dark hot space, felt like I channeled Travis Bickle.

Given the opportunity, how would you change New York?

Having to work in it in the summer.

What's your current soundtrack to the city?

I’ve been having a Grateful Dead moment – a CD was left in the car I drove a lot..

By Jen Carlson in Interview. All photos by Sam Horine.

Source : gothamist.com

Sunday, September 23, 2007

The 00s- The History of a Decade That Has Not Yet Been Named

Notes from a continuous conversation between Stéphanie Moisdon and Hans-Ulrich Obrist (selections) for the Lyon Biennial.

THE PLOT

“To construct history is the atheist equivalent of a prayer,” says historian Paul Veyne, who conceives of the writing of history not as a scientific exercise but as a modelling of the explosive satellisation of knowledge, as the constructing of plots, as a method of investigation drawing on traces, facts, clues, accidents and anecdotes. Here this methodical approach serves as a road map, with the players’ different proposals forming a mass of plots, directions and unanticipated adventures.

The resultant multiplicity of stories and characters produces an exploded time frame,a series of interruptions in which chance endlessly changes the destiny andcountenance of an exhibition transformed into an enormous machination, the locus of asecret conversation. However, the randomness this implies is neither the throw-of-the-dice kind nor the “psychological” variety cultivated by the Surrealists, but one generated by a system when the system taps into and takes over the creators’ intentions. For in the historical novel of the art of today, the question of the creator keeps coming up, and embracing other modalities of representation and of

distribution of subjectivities.

THE ARCHIPELAGO

For writer Edouard Glissant, biennials are closer in shape to continents – solid, imposing masses – than to the archipelago model of receptiveness, sharing and exchange. In his view, “The idea or the concept of a non-linear temporality implies the coexistence of several time zones, and at the same time leaves scope for a great range of contacts between these zones.” Seen as a zone of reciprocal contacts, then, the biennial can oscillate between the museum and the city, and between the city, its periphery and the world. It grows like a dynamic force field, radiating out through the whole city and beyond, embracing all sorts of organised partnerships at local,

national and international level – the House of Chaos just outside Lyon, the Bullukian Foundation, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Villeurbanne, Le Magasin in Grenoble, the Athens and Istanbul biennials, and so on – and even the territories of a Wikipedia-style Everyware community. Giving rise to self-run events, subsidiary exhibitions, and undreamed-of extensions, these joint ventures are also the opportunity to add new centres: let us not forget that the quest for an absolute centre that permeated and dominated a large part of the 20th century ultimately

resulted in a polyphony of centres in the 21st – a phenomenon not unrelated to the emergence and the power of biennials around the world. Glissant reminds us, too, that the homogenising forces of globalisation were countered in the 1990s by a proliferation of biennials – whose own homogenising impact led to the disappearance of difference. For despite their urge to breathe new life into the system, the curators of these biennials often did no more than reproduce obsolete models of visibility and geopolitical representation in a balancing act that reinforced the underpinnings of the global market.

THE MECHANISM

This project is a mechanism as defined by Giorgio Agamben: “The mechanism is a network of diverse elements embracing virtually all things, whether discursive or not: discourse, institutions, edifices and aesthetic and philosophical propositions. A mechanism always has a concrete strategic function and is always part of a relationship between power and knowledge.” Within such mechanisms – on which our existences sometimes depend – the question thus becomes: what strategies must we adopt in the daily struggle that links us to them? At a time when we are all faced with the need to get back to the possibilities of appropriate usage, the practicality of play – that purposeless children’s play that allows for the renewal of the

function of every object – becomes the instrument for new ways of doing things. The game space – with the exhibition space – is that of the proliferation of stories and usages, in which the rules ineluctably lead the participants to make choices. The game is never gratuitous, for it makes truly available that which was previously only accessible. To player and viewer alike it makes available the usage of the rules – the means of inventing a mythology of the present. “Each time,” says Agamben, “we have to wrench back from the mechanisms the possibility of usage they have taken captive. The profanation of the unprofanable is the political task of the coming generation.”

Stéphanie Moisdon and Hans-Ulrich Obrist

THE PLOT

“To construct history is the atheist equivalent of a prayer,” says historian Paul Veyne, who conceives of the writing of history not as a scientific exercise but as a modelling of the explosive satellisation of knowledge, as the constructing of plots, as a method of investigation drawing on traces, facts, clues, accidents and anecdotes. Here this methodical approach serves as a road map, with the players’ different proposals forming a mass of plots, directions and unanticipated adventures.

The resultant multiplicity of stories and characters produces an exploded time frame,a series of interruptions in which chance endlessly changes the destiny andcountenance of an exhibition transformed into an enormous machination, the locus of asecret conversation. However, the randomness this implies is neither the throw-of-the-dice kind nor the “psychological” variety cultivated by the Surrealists, but one generated by a system when the system taps into and takes over the creators’ intentions. For in the historical novel of the art of today, the question of the creator keeps coming up, and embracing other modalities of representation and of

distribution of subjectivities.

THE ARCHIPELAGO

For writer Edouard Glissant, biennials are closer in shape to continents – solid, imposing masses – than to the archipelago model of receptiveness, sharing and exchange. In his view, “The idea or the concept of a non-linear temporality implies the coexistence of several time zones, and at the same time leaves scope for a great range of contacts between these zones.” Seen as a zone of reciprocal contacts, then, the biennial can oscillate between the museum and the city, and between the city, its periphery and the world. It grows like a dynamic force field, radiating out through the whole city and beyond, embracing all sorts of organised partnerships at local,

national and international level – the House of Chaos just outside Lyon, the Bullukian Foundation, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Villeurbanne, Le Magasin in Grenoble, the Athens and Istanbul biennials, and so on – and even the territories of a Wikipedia-style Everyware community. Giving rise to self-run events, subsidiary exhibitions, and undreamed-of extensions, these joint ventures are also the opportunity to add new centres: let us not forget that the quest for an absolute centre that permeated and dominated a large part of the 20th century ultimately

resulted in a polyphony of centres in the 21st – a phenomenon not unrelated to the emergence and the power of biennials around the world. Glissant reminds us, too, that the homogenising forces of globalisation were countered in the 1990s by a proliferation of biennials – whose own homogenising impact led to the disappearance of difference. For despite their urge to breathe new life into the system, the curators of these biennials often did no more than reproduce obsolete models of visibility and geopolitical representation in a balancing act that reinforced the underpinnings of the global market.

THE MECHANISM

This project is a mechanism as defined by Giorgio Agamben: “The mechanism is a network of diverse elements embracing virtually all things, whether discursive or not: discourse, institutions, edifices and aesthetic and philosophical propositions. A mechanism always has a concrete strategic function and is always part of a relationship between power and knowledge.” Within such mechanisms – on which our existences sometimes depend – the question thus becomes: what strategies must we adopt in the daily struggle that links us to them? At a time when we are all faced with the need to get back to the possibilities of appropriate usage, the practicality of play – that purposeless children’s play that allows for the renewal of the

function of every object – becomes the instrument for new ways of doing things. The game space – with the exhibition space – is that of the proliferation of stories and usages, in which the rules ineluctably lead the participants to make choices. The game is never gratuitous, for it makes truly available that which was previously only accessible. To player and viewer alike it makes available the usage of the rules – the means of inventing a mythology of the present. “Each time,” says Agamben, “we have to wrench back from the mechanisms the possibility of usage they have taken captive. The profanation of the unprofanable is the political task of the coming generation.”

Stéphanie Moisdon and Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Friday, September 21, 2007

Installing Singing Sovietness at the Institute of Contemporary Art

Lyon Biennale 07

LISTE DES JOUEURS ET DES ARTISTES

Saâdane Afif

Peio Aguirre artiste invité: Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa

Yves Aupetitallot artiste invitée: Una Szeemann

Pierre Bal-Blanc artistes invités: Annie Vigier & Franck Apertet

Jérôme Bel

Daniel Birnbaum artiste invité: Tomas Saraceno

Thomas Boutoux artiste invité: Jia Zhang-ke

Giovanni Carmine artiste invitée: Norma Jeane

Paul Chan Jay Sanders

Claire Fontaine

Mathieu Copeland artiste invitée: Mai-Thu Perret

Stuart Comer artiste invitée: Hilary Lloyd

Trisha Donnelly

Jacob Fabricius artiste invité: Dave Hullfish Bailey

Hu Fang artiste invitée: Cao Fei

Lauri Firstenberg artiste invité: Adrià Julià

Jean Pascal Flavien

Massimiliano Gioni artiste invité: Urs Fischer

Julieta Gonzalez artiste invité: Simon Starling

Suman Gopinath artiste invitée: Sheela Gowda

Francesca Grassi artiste invité: Ryan Gander

Hou Hanru artiste invité: Ömer Ali Kazma

Dorothea von Hantelmann artiste invité: James Coleman

Jens Hoffmann artiste invité: Tino Sehgal

Michel Houellebecq

Pierre Joseph

Stefan Kalmar invité: Dot Dot Dot Magazine

Rem Koolhaas

Marta Kuzma artiste invité: Thomas Bayrle

Pi Li artiste invité: Liu Wei

Francesco Manacorda artiste invité: Armando Andrade, Tudela

Raimundas Malasauskas artiste invité: Darius Miksys

Francis McKee artiste invitée: Jumana Emil Abboud

Markus Miessen

Tom Morton artiste invité: Charles Avery

Joanna Mytkowska artiste invitée: Minerva Cuevas

Sean O’Toole artiste invité: James Webb

Vincent Pécoil artiste invité: Ohad Meromi

Adriano Pedrosa artiste invité: Marcellvs L.

Natasa Petresin artistes invités: Nomeda et Gediminas Urbonas

Susanne Pfeffer artiste invitée: Annette Kelm

Anne Pontégnie artiste invité: Kelley Walker

Willem de Rooij

Scott Rothkopf artiste invité: Wade Guyton

Beatrix Ruf artiste invitée: Keren Cytter

Josh Smith

Trevor Smith artiste invité: Brian Jungen

Pooja Sood artiste invitée: Shilpa Gupta

Rachael Thomas artiste invité: Gerard Byrne

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Nicolas Trembley artiste invité: Christian Holstad

Eric Troncy artiste invité: David Hamilton

Philippe Vergne artiste invitée: Ranjani Shettar

Gilbert Vicario artiste invité: Erick Beltran

Andrea Viliani artiste invité: Seth Price

Jochen Volz artiste invitée: Cinthia Marcelle

Hamza Walker artistes invités: Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla

Xenia Kalpaktsoglou, Poka-Yio, augustine Zenakos artiste invité: Kostis Velonis

Tirdad Zolghadr invité: Museum of American Art

E-flux video rental Fondation Bullukian

Thursday, September 20, 2007

Athens biennial 07

Nikos Kessanlis -proposition pour une nouvelle sculpture grecque, 1964

the artists of "Destroy Athens"

Adbusters

Assume Vivid Astro Focus

Aidas Bareikis

Marc Bijl

John Bock

Olaf Breuning

Kimberly Clark

Annelise Coste

Kajsa Dahlberg

Peter Dreher

The Erasers

Chris Evans

Stelios Faitakis

Jan Freuchen

HobbypopMUSEUM

Narve Hovdenakk

Derek Jarman

Folkert de Jong

Vassilis Karouk

Omer Ali Kazma

John Kleckner

Terence Koh

Edward Lipski

Lotte Konow Lund

Mark Manders

Bjarne Melgaard

Ciprian Muresan

Eleni Mylonas

Olaf Nicolai

The Otolith Group

Erkan Ozgen

Torbjorn Rodland

Julian Rosefeldt

Georgia Sagri

Yorgos Sapountzis

Yiannis Savvidis

Santiago Sierra

Martin Skauen

Eva Stephani

Temporary Services

Thanassis Totsikas

Stephanos Tsivopoulos

Jannis Varelas

Void Network

Eva Vretzaki

Bernhard Willhelm

How to endure

Charles Avery

Miguel Calderon

Allen Ginsberg

Loris Greaud

Roger Hiorns

Matthew Day Jackson

Germaine Kruip

Grant Morrison &

Frank Quitely

Olivia Plender

Maaike Schoorel

Young Athenians

Tam A

Kim Coleman

Craig Coulthard

Keith Farquhar

Tommy Grace

Jenny Hogarth

Darius Jones

David MacLean

John Mullen

Ellen Munro

One O'Clock Gun

Lee O'Connor

Katie Orton

Kate Owens

Sophie Rogers

Robin Scott

Cathy Stafford

Lucy Mackenzie

Alastair Fairweather

..and the Gallery Shows as a parallel event

Rita Ackerman, David Adamo, Graham Anderson, Dimitris Antonitsis, Scott Arford, Anastasios Argianas, Assume Vivid Astro Focus, Dan Attoe, Charles Avery, b., Rossina Baltatzi, Aidas Bareikis, Barns, Richard Battye, Marc Bell, Brian Belott, Marc Bijl, Rebecca Bird, Blexbolex, Joe Bradley, Melissa Brown, Stefan Bruggemann, Guillermo Caivano, Miguel Calderon, CF, Brian Chippendale, Savvas Christodoulides, Eleni Christodoulou, Kimberly Clark, Kim Coleman, Dan Colen, Matt Connors, Bjorn Copeland, Costes, Craig Coulthard, Lydia Dambassina, Matthew Darbyshire, Matthew Day Jackson, Dezo, Amy Dicke, Christina Dimitriadis, Lucy Dodd, Kaye Donachie, Julie Doucet, Anastasia Douka, Dreyk, Stef Driesen, Eros, errorism (crew), Jan Fabre, Stelios Faitakis, Keith Farquhar, Theodore Fivel, Frederic Fleury, Frederic D, Vasso Gavaisse, Michael Gendreau, Alexandros Georgiou, Steve Gianakos, Allen Ginsberg, Tomoo Gokita, Leif Goldberg, Nan Goldin, Delia Gonzalez, Tommy Grace, Loris Greaud, Matt Greene, Group Mel-air, Mohammed Hamdi, Thomas Helbig, Uwe Henneken, Federico Herrero, Melanie Hill, Roger Hiorns, Jenny Hogarth, Jungil Hong, Mustafa Hulusi, Icnoc, Joad, Jola, Ben Jones, Geoffrey Jones, Darius Jones, Liz Kang, Antimatter/ Z. Karkowski, Dionisis Kavallieratos, David Kennedy Cutler, Eleni Kamma, Nikos Katsaounis, Kebzer, Danius Kesminas, John Kleckner, Terence Koh, Sotirios Kotoulas, Marcelo Krasilcic, Germaine Kruip, Alex Kwartler, Bruce LaBruce, Matthieu Laurette, Paul Lee, Lucas Lenglet, Lifo (crew), Los Super Elegantes, Panayiotis Loukas, Nate Lowman, Keith MacIsaac, David MacLean, Sakura Maku, Miltos Manetas, Nikos Markou, Eddie Martinez, Keith McCulloch, Taylor McKimens, Ryan McLaughlin, Irini Miga, Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely, John Mullen, Ellen Munro, Robert Nixon, Lee O'Connor, OFK (crew), One O'Clock Gun, Katie Orton, Kate Owens, Gary Panter, Nikos Papadimitriou, Ilias Papailiakis, Paper Rad, Eftihis Patsourakis, Paris Petridis, Panyotis, Dave Phillips, Oliver Pietsch, pixel, Olivia Plender, Angelo Plessas, Lila Polenaki, Qbrick, Quits, Phillippe Ramette, Stefan Rinck, Kirstine Roepstorff, Andrew Rogers, Sophie Rogers, Erin Rosenthal, Gavin Russom, Michael Sailstorfer, Dean Sameshima, David Sandlin, Liliana Sanguino, Frank Santoro, Yorgos Sapountzis, Hannes Schmidt, Maaike Schoorel, Robin Schulie, Tilo Schulz, Robin Scott, Mindy Shapero, Patrick Smith, Agathe Snow, Dash Snow, Spike69, Cathy Stafford, Anton Stoianov, Matthew Stone, Spencer Sweeney, SRS (crew), Tam A, Panayotis Terzis, Matthew Thurber, Till Death (crew), Sophie-Terese Trenka-Dalton, Su-Mei Tse, V/VM, UDK (crew), Dimitra Vamiali, Iris van Dongen, Jannis Varelas, Allyson Vieira, Vee, Garth Weiser, WFC (crew), Michael Williams, Norbert Witzgall, Clare Woods, Andrew Jeffrey Wright, AaroonYoung, Vita Zaman , represented by the following galleries : AD Gallery (GR), Blow de la Barra (UK), The Breeder (GR), Rebecca Camhi Gallery (GR), Eleni Koroneou Gallery (GR), Loraini Alimantiri - Gazon Rouge (GR),, IBID Projects (UK), Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Centre (GR), Johann Konig (DE), Andreas Melas Presents (GR), Nice & Fit (DE) , Peres Projects (USA/DE), Rodeo (TU), Spencer Brownstone (USA), Vamiali's (GR), Xippas Gallery (GR)

www.athensbiennial.org

www.remapkm.com

Friday, September 14, 2007

He's Watching You

This striking poster was designed in 1942 by artist Glenn Grohe for the Office of Emergency Management. It shows the menacing, shadowy figure of a German soldier peering directly at the viewer. It was intended to motivate adherence to wartime rules about secrecy in the industrial sector.

However, a 1942 government survey of the American public revealed that the poster was often misunderstood. Many people perceived the stylised German helmet as the Liberty Bell, while some factory workers mistakenly believed "he" to be the "boss." Because of this type of issue, the U.S. Office of War Information was created in June 1942 to review and approve the design and distribution of government war posters.

It has been noted that the figure closely resembles Darth Vader, the sinister character in Star Wars, whose appearance may have been influenced by this poster.

Source:

www.olive-drab.com

Poe's Ideal Furniture

With this essay Poe becomes one of the first theorists of the interior decoration or even architectural design. His humorous tone is incredible, especially when he insists that decoration in America has become a "mere parade of costly appurtenances" to create an "impression of the beautiful". But what is the most important is that the writer explains decoration in terms of an art activity.

The Philosophy of Furniture

"PHILOSOPHY," says Hegel, "is utterly useless and fruitless, and, for this very reason, is the sublimest of all pursuits, the most deserving of our attention, and the most worthy of our zeal" — a somewhat Coleridegy assertion, with a rivulet of deep meaning in a meadow of words. It would be wasting time to disentangle the paradox — and the more so as no one will deny that Philosophy has its merits, and is applicable to an infinity of purposes. There is reason, it is said, in the roasting of eggs, and there is philosophy even in furniture — a philosophy nevertheless which seems to be more imperfectly understood by Americans than by any civilized nation upon the face of the earth.

In the internal decoration, if not in the external architecture of their residences, the English are supreme. The Italians have but little sentiment beyond marbles and colours. In France, meliora probant, deteriora sequuntur — the people are too much a race of gadabouts to study and maintain those household proprieties of which, indeed, they have a delicate appreciation, or at least the elements of a proper sense. The Chinese and most of the eastern races have a warm but inappropriate fancy. The Scotch are poor decorists. The Dutch have merely a vague idea that a curtain is not a cabbage. In Spain they are all curtains — a nation of hangmen. The Russians no [[do]] not furnish. The Hottentots and Kickapoos are very well in their way. The Yankees alone are preposterous.

How this happens, it is not difficult to see. We have no aristocracy of blood, and having therefore as a natural, and indeed as an inevitable thing, fashioned for ourselves an aristocracy of dollars, the display of wealth has here to take the place and perform the office of the heraldic display in monarchical countries. By a transition readily understood, and which might have been easily foreseen, we have been brought to merge in simple show our notions of taste itself. To speak less abstractedly. In England, for example, no mere parade of costly appurtenances would be so likely as with us, to create an impression of the beautiful in respect to the appurtenances themselves — or of taste as respects the proprietor: — this for the reason, first, that wealth is not, in England, the loftiest object of ambition as constituting a nobility; and secondly, that there, the true nobility of blood rather avoids than affects costliness in which a parvenu rivalry may be successfully attempted, confining itself within the rigorous limits, and to the analytical investigation, of legitimate taste. The people will naturally imitate the nobles, and the result is a thorough diffusion of a right feeling. But in America, dollars being the supreme insignia of aristocracy, their display may be said, in general terms, to be the sole means of the aristocratic distinction; and the populace, looking up for models, are insensibly led to confound the two entirely separate ideas of magnificence and beauty. In short, the cost of an article of furniture has at length come to be, with us, nearly the sole test of its merit in a decorative point of view — and this test, once established, has led the way to many analogous errors, readily traceable to the one primitive folly.

There could be scarcely any thing more directly offensive to the eye of an artist than the interior of what is termed in the United States, a well-furnished apartment. Its most usual defect is a want of keeping. We speak of the keeping of a room as we would of the keeping of a picture — for both the picture and the room are amenable to those undeviating principles which regulate all varieties of art; and very nearly the same laws by which we decide upon the higher merits of a painting, suffice for a decision upon the adjustment of a chamber. A want of keeping is observable sometimes in the character of the several pieces of furniture, but generally in their colours or modes of adaptation to use. Very often the eye is offended by their inartistic arrangement. Straight lines are too prevalent — too uninterruptedly continued — or clumsily interrupted at right angles. If curved lines occur, they are repeated into unpleasant uniformity. Undue precision spoils the appearance of many a room.

Curtains are rarely well disposed, or well chosen in respect to the other decorations. With formal furniture, curtains are out of place; and an excessive volume of drapery of any kind is, under any circumstance, irreconcilable with good taste — the proper quantum, as well as the proper adjustment, depends upon the character of the general effect.

Carpets are better understood of late than of ancient days, but we still very frequently err in their patterns and colours. A carpet is the soul of the apartment. From it are deduced not only the hues but the forms of all objects incumbent. A judge at common law may be an ordinary man; a good judge of a carpet must be a genius. Yet I have heard fellows discourse of carpets with the visage of a sheep in reverie — "d'un mouton qui rêve" — who should not and who could not be entrusted with the management of their own moustachios. Every one knows that a large floor should have a covering of large figures, and a small one must have a covering of small — yet this is not all the knowledge in the world. As regards texture, the Saxony is alone admissible. Brussels is the preterpluperfect tense of fashion, and Turkey is taste in its dying agonies. Touching pattern — a carpet should not be bedizzened out like a Riccaree Indian — all red chalk, yellow ochre, and cock's feathers. In brief, distinct grounds and vivid circular figures, of no meaning, are here Median laws. The abomination of flowers, or representations of well-known objects of any kind, should never be endured within the limits of Christendom. Indeed, whether on carpets, or curtains, or paper-hangings, or ottoman coverings, all upholstery of this nature should be rigidly Arabesque. Those antique floor-cloths which are still seen occasionally in the dwellings of the rabble — cloths of huge, sprawling, and radiating devices, stripe-interspersed, and glorious with all hues, among which no ground is intelligible — are but the wicked invention of a race of time-servers and money-lovers — children of Baal and worshippers of Mammon — men who, to save trouble of thought and exercise of fancy, first cruelly invented the Kaleidoscope, and then established a patent company to twirl it by steam.

Glare is a leading error in the philosophy of American household decoration — an error easily recognised as deduced from the perversion of taste just specified., We are violently enamoured of gas and of glass. The former is totally inadmissible within doors. Its harsh and unsteady light offends. No one having both brains and eyes will use it. A mild, or what artists term a cool light, with its consequent warm shadows, will do wonders for even an ill-furnished apartment. Never was a more lovely thought than that of the astral lamp. We mean, of course, the astral lamp proper — the lamp of Argand, with its original plain ground-glass shade, and its tempered and uniform moonlight rays. The cut-glass shade is a weak invention of the enemy. The eagerness with which we have adopted it, partly on account of its flashiness, but principally on account of its greater rest, is a good commentary on the proposition with which we began. It is not too much to say, that the deliberate employer of a cut-glass shade, is either radically deficient in taste, or blindly subservient to the caprices of fashion. The light proceeding from one of these gaudy abominations is unequal broken, and painful. It alone is sufficient to mar a world of good effect in the furniture subjected to its influence. Female loveliness, in especial, is more than one-half disenchanted beneath its evil eye.

In the matter of glass, generally, we proceed upon false principles. Its leading feature is glitter — and in that one word how much of all that is detestable do we express ! Flickering, unquiet lights, are sometimes pleasing — to children and idiots always so — but in the embellishment of a room they should be scrupulously avoided. In truth, even strong steady lights are inadmissible. The huge and unmeaning glass chandeliers, prism-cut, gas-lighted, and without shade, which dangle in our most fashionable drawing-rooms, may be cited as the quintessence of all that is false in taste or preposterous in folly.

The rage for glitter—because its idea has become as we before observed, confounded with that of magnificence in the abstract—has led us, also, to the exaggerated employment of mirrors. We line our dwellings with great British plates, and then imagine we have done a fine thing. Now the slightest thought will be sufficient to convince any one who has an eye at all, of the ill effect of numerous looking-glasses, and especially of large ones. Regarded apart from its reflection, the mirror presents a continuous, flat, colourless, unrelieved surface, — a thing always and obviously unpleasant. Considered as a reflector, it is potent in producing a monstrous and odious uniformity: and the evil is here aggravated, not in merely direct proportion with the augmentation of its sources, but in a ratio constantly increasing. In fact, a room with four or five mirrors arranged at random, is, for all purposes of artistic show, a room of no shape at all. If we add to this evil, the attendant glitter upon glitter, we have a perfect farrago of discordant and displeasing effects. The veriest bumpkin, on entering an apartment so bedizzened, would be instantly aware of something wrong, although he might be altogether unable to assign a cause for his dissatisfaction. But let the same person be led into a room tastefully furnished, and he would be startled into an exclamation of pleasure and surprise.

It is an evil growing out of our republican institutions, that here a man of large purse has usually a very little soul which he keeps in it. The corruption of taste is a portion or a pendant of the dollar-manufac sure. As we grow rich, our ideas grow rusty. It is, therefore, not among our aristocracy that we must look (if at all, in Appallachia), for the spirituality of a British boudoir. But we have seen apartments in the tenure of Americans of moderate means, which, in negative merit at least, might vie with any of the or-molu'd cabinets of our friends across the water. Even now, there is present to our mind's eye a small and not, ostentatious chamber with whose decorations no fault can be found. The proprietor lies asleep on a sofa — the weather is cool — the time is near midnight: I will make a sketch of the room ere he awakes. It is oblong — some thirty feet in length and twenty-five in breadth — a shape affording the best (ordinary) opportunities for the adjustment of furniture. It has but one door — by no means a wide one — which is at one end of the parallelogram, and but two windows, which are at the other. These latter are large, reaching down to the floor — have deep recesses — and open on an Italian veranda. Their panes are of a crimson-tinted glass, set in rose-wood framings, more massive than usual. They are curtained within the recess, by a thick silver tissue adapted to the shape of the window, and hanging loosely in small volumes. Without the recess are curtains of an exceedingly rich crimson silk, fringed with a deep network of gold, and lined with silver tissue, which is the material of the exterior blind. There are no cornices; but the folds of the whole fabric (which are sharp rather than massive, and have an airy appearance), issue from beneath a broad entablature of rich gilt-work, which encircles the room at the junction of the ceiling and walls. The drapery is thrown open also, or closed, by means of a thick rope of gold loosely enveloping it, and resolving itself readily into a knot; no pins or other such devices are apparent. The colours of the curtains and their fringe — the tints of crimson and gold — appear everywhere in profusion, and determine the character of the room. The carpet — of Saxony material — is quite half an inch thick, and is of the same crimson ground, relieved simply by the appearance of a gold cord (like that festooning the curtains) slightly relieved above the surface of the ground, and thrown upon it in such a manner as to form a succession of short irregular curves — one occasionally overlaying the other. The walls are prepared with a glossy paper of a silver gray tint, spotted with small Arabesque devices of a fainter hue of the prevalent crimson. Many paintings relieve the expanse of paper. These are chiefly landscapes of an imaginative cast—such as the fairy grottoes of Stanfield, or the lake of the Dismal Swamp of Chapman. There are, nevertheless, three or four female heads, of an ethereal beauty—portraits in the manner of Sully. The tone of each picture is warm, but dark. There are no "brilliant effects." Repose speaks in all. Not one is of small size. Diminutive paintings give that spotty look to a room, which is the blemish of so many a fine work of Art overtouched. The frames are broad but not deep, and richly carved, without being dulled or filagreed. They have the whole lustre of burnished gold. They lie flat on the walls, and do not hang off with cords. The designs themselves are often seen to better advantage in this latter position, but the general appearance of the chamber is injured. But one mirror — and this not a very large one — is visible. In shape it is nearly circular — and it is hung so that a reflection of the person can be obtained from it in none of the ordinary sitting-places of the room. Two large low sofas of rosewood and crimson silk, gold-flowered, form the only seats, with the exception of two light conversation chairs, also of rose-wood. There is a pianoforte (rose-wood, also), without cover, and thrown open. An octagonal table, formed altogether of the richest gold-threaded marble, is placed near one of the sofas. This is also without cover — the drapery of the curtains has been thought sufficient.. Four large and gorgeous Sevres vases, in which bloom a profusion of sweet and vivid flowers, occupy the slightly rounded angles of the room. A tall candelabrum, bearing a small antique lamp with highly perfumed oil, is standing near the head of my sleeping friend. Some light and graceful hanging shelves, with golden edges and crimson silk cords with gold tassels, sustain two or three hundred magnificently bound books. Beyond these things, there is no furniture, if we except an Argand lamp, with a plain crimson-tinted ground glass shade, which depends from the lofty vaulted ceiling by a single slender gold chain, and throws a tranquil but magical radiance over all.

Edgar Allan Poe, "The Philosophy of Furniture," Burton's Gentleman's Magazine, May 1840.

The Philosophy of Furniture

"PHILOSOPHY," says Hegel, "is utterly useless and fruitless, and, for this very reason, is the sublimest of all pursuits, the most deserving of our attention, and the most worthy of our zeal" — a somewhat Coleridegy assertion, with a rivulet of deep meaning in a meadow of words. It would be wasting time to disentangle the paradox — and the more so as no one will deny that Philosophy has its merits, and is applicable to an infinity of purposes. There is reason, it is said, in the roasting of eggs, and there is philosophy even in furniture — a philosophy nevertheless which seems to be more imperfectly understood by Americans than by any civilized nation upon the face of the earth.

In the internal decoration, if not in the external architecture of their residences, the English are supreme. The Italians have but little sentiment beyond marbles and colours. In France, meliora probant, deteriora sequuntur — the people are too much a race of gadabouts to study and maintain those household proprieties of which, indeed, they have a delicate appreciation, or at least the elements of a proper sense. The Chinese and most of the eastern races have a warm but inappropriate fancy. The Scotch are poor decorists. The Dutch have merely a vague idea that a curtain is not a cabbage. In Spain they are all curtains — a nation of hangmen. The Russians no [[do]] not furnish. The Hottentots and Kickapoos are very well in their way. The Yankees alone are preposterous.

How this happens, it is not difficult to see. We have no aristocracy of blood, and having therefore as a natural, and indeed as an inevitable thing, fashioned for ourselves an aristocracy of dollars, the display of wealth has here to take the place and perform the office of the heraldic display in monarchical countries. By a transition readily understood, and which might have been easily foreseen, we have been brought to merge in simple show our notions of taste itself. To speak less abstractedly. In England, for example, no mere parade of costly appurtenances would be so likely as with us, to create an impression of the beautiful in respect to the appurtenances themselves — or of taste as respects the proprietor: — this for the reason, first, that wealth is not, in England, the loftiest object of ambition as constituting a nobility; and secondly, that there, the true nobility of blood rather avoids than affects costliness in which a parvenu rivalry may be successfully attempted, confining itself within the rigorous limits, and to the analytical investigation, of legitimate taste. The people will naturally imitate the nobles, and the result is a thorough diffusion of a right feeling. But in America, dollars being the supreme insignia of aristocracy, their display may be said, in general terms, to be the sole means of the aristocratic distinction; and the populace, looking up for models, are insensibly led to confound the two entirely separate ideas of magnificence and beauty. In short, the cost of an article of furniture has at length come to be, with us, nearly the sole test of its merit in a decorative point of view — and this test, once established, has led the way to many analogous errors, readily traceable to the one primitive folly.

There could be scarcely any thing more directly offensive to the eye of an artist than the interior of what is termed in the United States, a well-furnished apartment. Its most usual defect is a want of keeping. We speak of the keeping of a room as we would of the keeping of a picture — for both the picture and the room are amenable to those undeviating principles which regulate all varieties of art; and very nearly the same laws by which we decide upon the higher merits of a painting, suffice for a decision upon the adjustment of a chamber. A want of keeping is observable sometimes in the character of the several pieces of furniture, but generally in their colours or modes of adaptation to use. Very often the eye is offended by their inartistic arrangement. Straight lines are too prevalent — too uninterruptedly continued — or clumsily interrupted at right angles. If curved lines occur, they are repeated into unpleasant uniformity. Undue precision spoils the appearance of many a room.

Curtains are rarely well disposed, or well chosen in respect to the other decorations. With formal furniture, curtains are out of place; and an excessive volume of drapery of any kind is, under any circumstance, irreconcilable with good taste — the proper quantum, as well as the proper adjustment, depends upon the character of the general effect.

Carpets are better understood of late than of ancient days, but we still very frequently err in their patterns and colours. A carpet is the soul of the apartment. From it are deduced not only the hues but the forms of all objects incumbent. A judge at common law may be an ordinary man; a good judge of a carpet must be a genius. Yet I have heard fellows discourse of carpets with the visage of a sheep in reverie — "d'un mouton qui rêve" — who should not and who could not be entrusted with the management of their own moustachios. Every one knows that a large floor should have a covering of large figures, and a small one must have a covering of small — yet this is not all the knowledge in the world. As regards texture, the Saxony is alone admissible. Brussels is the preterpluperfect tense of fashion, and Turkey is taste in its dying agonies. Touching pattern — a carpet should not be bedizzened out like a Riccaree Indian — all red chalk, yellow ochre, and cock's feathers. In brief, distinct grounds and vivid circular figures, of no meaning, are here Median laws. The abomination of flowers, or representations of well-known objects of any kind, should never be endured within the limits of Christendom. Indeed, whether on carpets, or curtains, or paper-hangings, or ottoman coverings, all upholstery of this nature should be rigidly Arabesque. Those antique floor-cloths which are still seen occasionally in the dwellings of the rabble — cloths of huge, sprawling, and radiating devices, stripe-interspersed, and glorious with all hues, among which no ground is intelligible — are but the wicked invention of a race of time-servers and money-lovers — children of Baal and worshippers of Mammon — men who, to save trouble of thought and exercise of fancy, first cruelly invented the Kaleidoscope, and then established a patent company to twirl it by steam.

Glare is a leading error in the philosophy of American household decoration — an error easily recognised as deduced from the perversion of taste just specified., We are violently enamoured of gas and of glass. The former is totally inadmissible within doors. Its harsh and unsteady light offends. No one having both brains and eyes will use it. A mild, or what artists term a cool light, with its consequent warm shadows, will do wonders for even an ill-furnished apartment. Never was a more lovely thought than that of the astral lamp. We mean, of course, the astral lamp proper — the lamp of Argand, with its original plain ground-glass shade, and its tempered and uniform moonlight rays. The cut-glass shade is a weak invention of the enemy. The eagerness with which we have adopted it, partly on account of its flashiness, but principally on account of its greater rest, is a good commentary on the proposition with which we began. It is not too much to say, that the deliberate employer of a cut-glass shade, is either radically deficient in taste, or blindly subservient to the caprices of fashion. The light proceeding from one of these gaudy abominations is unequal broken, and painful. It alone is sufficient to mar a world of good effect in the furniture subjected to its influence. Female loveliness, in especial, is more than one-half disenchanted beneath its evil eye.

In the matter of glass, generally, we proceed upon false principles. Its leading feature is glitter — and in that one word how much of all that is detestable do we express ! Flickering, unquiet lights, are sometimes pleasing — to children and idiots always so — but in the embellishment of a room they should be scrupulously avoided. In truth, even strong steady lights are inadmissible. The huge and unmeaning glass chandeliers, prism-cut, gas-lighted, and without shade, which dangle in our most fashionable drawing-rooms, may be cited as the quintessence of all that is false in taste or preposterous in folly.

The rage for glitter—because its idea has become as we before observed, confounded with that of magnificence in the abstract—has led us, also, to the exaggerated employment of mirrors. We line our dwellings with great British plates, and then imagine we have done a fine thing. Now the slightest thought will be sufficient to convince any one who has an eye at all, of the ill effect of numerous looking-glasses, and especially of large ones. Regarded apart from its reflection, the mirror presents a continuous, flat, colourless, unrelieved surface, — a thing always and obviously unpleasant. Considered as a reflector, it is potent in producing a monstrous and odious uniformity: and the evil is here aggravated, not in merely direct proportion with the augmentation of its sources, but in a ratio constantly increasing. In fact, a room with four or five mirrors arranged at random, is, for all purposes of artistic show, a room of no shape at all. If we add to this evil, the attendant glitter upon glitter, we have a perfect farrago of discordant and displeasing effects. The veriest bumpkin, on entering an apartment so bedizzened, would be instantly aware of something wrong, although he might be altogether unable to assign a cause for his dissatisfaction. But let the same person be led into a room tastefully furnished, and he would be startled into an exclamation of pleasure and surprise.

It is an evil growing out of our republican institutions, that here a man of large purse has usually a very little soul which he keeps in it. The corruption of taste is a portion or a pendant of the dollar-manufac sure. As we grow rich, our ideas grow rusty. It is, therefore, not among our aristocracy that we must look (if at all, in Appallachia), for the spirituality of a British boudoir. But we have seen apartments in the tenure of Americans of moderate means, which, in negative merit at least, might vie with any of the or-molu'd cabinets of our friends across the water. Even now, there is present to our mind's eye a small and not, ostentatious chamber with whose decorations no fault can be found. The proprietor lies asleep on a sofa — the weather is cool — the time is near midnight: I will make a sketch of the room ere he awakes. It is oblong — some thirty feet in length and twenty-five in breadth — a shape affording the best (ordinary) opportunities for the adjustment of furniture. It has but one door — by no means a wide one — which is at one end of the parallelogram, and but two windows, which are at the other. These latter are large, reaching down to the floor — have deep recesses — and open on an Italian veranda. Their panes are of a crimson-tinted glass, set in rose-wood framings, more massive than usual. They are curtained within the recess, by a thick silver tissue adapted to the shape of the window, and hanging loosely in small volumes. Without the recess are curtains of an exceedingly rich crimson silk, fringed with a deep network of gold, and lined with silver tissue, which is the material of the exterior blind. There are no cornices; but the folds of the whole fabric (which are sharp rather than massive, and have an airy appearance), issue from beneath a broad entablature of rich gilt-work, which encircles the room at the junction of the ceiling and walls. The drapery is thrown open also, or closed, by means of a thick rope of gold loosely enveloping it, and resolving itself readily into a knot; no pins or other such devices are apparent. The colours of the curtains and their fringe — the tints of crimson and gold — appear everywhere in profusion, and determine the character of the room. The carpet — of Saxony material — is quite half an inch thick, and is of the same crimson ground, relieved simply by the appearance of a gold cord (like that festooning the curtains) slightly relieved above the surface of the ground, and thrown upon it in such a manner as to form a succession of short irregular curves — one occasionally overlaying the other. The walls are prepared with a glossy paper of a silver gray tint, spotted with small Arabesque devices of a fainter hue of the prevalent crimson. Many paintings relieve the expanse of paper. These are chiefly landscapes of an imaginative cast—such as the fairy grottoes of Stanfield, or the lake of the Dismal Swamp of Chapman. There are, nevertheless, three or four female heads, of an ethereal beauty—portraits in the manner of Sully. The tone of each picture is warm, but dark. There are no "brilliant effects." Repose speaks in all. Not one is of small size. Diminutive paintings give that spotty look to a room, which is the blemish of so many a fine work of Art overtouched. The frames are broad but not deep, and richly carved, without being dulled or filagreed. They have the whole lustre of burnished gold. They lie flat on the walls, and do not hang off with cords. The designs themselves are often seen to better advantage in this latter position, but the general appearance of the chamber is injured. But one mirror — and this not a very large one — is visible. In shape it is nearly circular — and it is hung so that a reflection of the person can be obtained from it in none of the ordinary sitting-places of the room. Two large low sofas of rosewood and crimson silk, gold-flowered, form the only seats, with the exception of two light conversation chairs, also of rose-wood. There is a pianoforte (rose-wood, also), without cover, and thrown open. An octagonal table, formed altogether of the richest gold-threaded marble, is placed near one of the sofas. This is also without cover — the drapery of the curtains has been thought sufficient.. Four large and gorgeous Sevres vases, in which bloom a profusion of sweet and vivid flowers, occupy the slightly rounded angles of the room. A tall candelabrum, bearing a small antique lamp with highly perfumed oil, is standing near the head of my sleeping friend. Some light and graceful hanging shelves, with golden edges and crimson silk cords with gold tassels, sustain two or three hundred magnificently bound books. Beyond these things, there is no furniture, if we except an Argand lamp, with a plain crimson-tinted ground glass shade, which depends from the lofty vaulted ceiling by a single slender gold chain, and throws a tranquil but magical radiance over all.

Edgar Allan Poe, "The Philosophy of Furniture," Burton's Gentleman's Magazine, May 1840.

Labels:

design,

domesticity,

furniture,

modernism and individuality

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)