Extract

from Reina Sofía Museum brochure of the exhibition:

Emotional

Architecture: The Work as Strategy Mathias Goeritz (Danzig, now

Gdansk, 1915) was educated in the turbulent Berlin of the

inter-war period, in the midst of the rise of National

Socialism. During the Second World War and the subsequent Cold

War, Goeritz forged himself a multiple personality. He was first

a philosopher and historian and afterwards a painter, a

development which coincided with his period at the German

Consulate in the Spanish protectorate of Morocco. From 1945 to

1948, Goeritz was feverishly active in Spain as a cultural

promoter, and in 1949 he moved to Mexico, where he intensified

his dual activity as an artist and agitator. It was there that

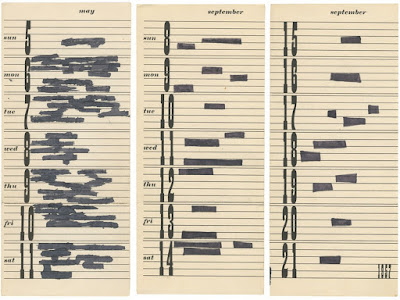

he condensed his aesthetic principles under the notion of

emotional architecture, which he was to apply not only to the

construction of buildings but also to painting, sculpture, graphics

and visual poetry. At a moment when figurative art and propaganda

dominated the art scene in Mexico, emotional architecture became

a device for confrontation, yet was well received by the politically

more conservative architectural profession. The increased number

of construction projects at that time meant that the potential for

commissions was very great. The work manifesto of emotional

architecture is the El Eco Experimental Museum which defines his

later production. Here Goeritz gathers various media (painting,

sculpture, furniture design and architecture) and works by

artists like Germán Cueto, Henry Moore and Carlos Mérida, his

own contributions being a monumental visual poem and the

formidable transposable sculpture of a twisted geometric snake,

transforming the open courtyard into a performance environment.

In

Torres de Ciudad Satélite (Towers of Satellite City), the

artist tests the limits of scale, artwork-viewer proximity, and

even modes of viewing. Five reinforced cement prisms of colossal

size foster the affective mobilization of the viewer and the

aestheticization of the effect, turning the work into a national

emblem of modernity. From then on, the use of a monumental scale

and the synthetic language of geometries, associated with the

idea of progress, identified Goeritz’s work as strategist and

agitator. A constructor of spatialities where new relations and

senses could be established, his art of mediations shakes the

institutions that validate art, such as the museum and criticism

(El Eco), artistic groups and the gallery (the group of Los

Hartos), and history and believe systems (the snake and the

pyramid or the cross and the star of David). Approaching his

oeuvre obliges us to engage with a work implicated with

cultural agency. The interest aroused today by the aspects of

circulation and reception in relational, contextual and

participative art contrasts with the development of that

creative modality of artistic mediation, that aesthetic of

commotion with which Goeritz experimented until his death in

1990.