How different things looked in 1900 and 2000. The end of the 19th century was drowned in fin de siècle gloom. The end of the 20th century was, on the contrary, exuberant. President Bush Sr triumphantly announced in 1991 that a "new world order" was coming into view in which "the principles of justice and fair play will protect the weak against the strong [and] freedom and humanity will find a home among nations … Enduring peace must be our mission." As the world was entering a new century of supposed peace and prosperity, I was hitting my half-century, a point of some pride and much foreboding. Melancholic retrospection and hopeful planning was the order of the day – for the world and me.

Globalisation, neoliberal economics and humanitarian cosmopolitanism were the contours of the new age. Economic interdependence, global communications, free trade, population and capital flows were bringing the world together, undermining the omnipotence of sovereignty and nation-state. A global civil society of multinational corporations, as well as international and non-governmental organisations, were to create the transnational solidarities necessary to protect against global risks.

Globalisation went hand in hand with the rise of neoliberal capitalism. The WTO and IMF imposed globally a model euphemistically known as the Washington consensus: pressure was put on developing states to deregulate and open their financial sector, privatise utilities and reduce welfare spending. These policies would, it was argued, unleash the economic potential of the developing world, hitherto blocked by inefficiency, corruption and socialism.

In the absence of a blueprint for this new arrangement, cosmopolitanism, a Greek philosophical idea revived by Kant in the 18th century and Kelsen and Habermas in the 20th, was presented as the world's destiny. Cosmopolitanism is globalisation with a human face. It promises a morally guided legal and institutional framework, the weakening if not abolition of the state form, and the strengthening of international institutions and civil society.

Iraq and Afghanistan were the last wars before this pending union of humankind. The end of history was therefore the triumph of historicism: nothing outside or beyond the dominant order could be used to criticise or resist it. Cosmopolitanism – bound by international law and human rights – was apparently here to stay; its principles could no longer be challenged. The only task left to politics was redistributions of power and wealth at the margins.

This was the great utopia at the end of the 20th century, a liberal fantasy as comprehensive as anything Christianity or Marxism had ever imagined. Embarrassingly, despite routine denunciations, it was accepted by people on the liberal left, like me. If the world cannot be changed, the argument went, the left should concentrate on small-scale projects, moral concerns and the protection of vulnerable identities. Multiculturalism could replace radical change, membership of Amnesty that of political organisations.

At the end of the first decade of the millennium, every aspect of this fantasy has been reversed. If this was a new world order, it was the shortest in history. "New deadly challenges have emerged from rogue states and terrorists," wrote Bush Jr in 2002, 10 years after his father's announcement. "We will not hesitate to act alone, if necessary, to exercise our right of self-defence by acting pre-emptively." Enduring peace became perpetual war. History returned with a vengeance.

Let me mention the recent signs of this "bonfire of falsities": 1. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars have left a bitter taste of political and moral decadence. The continuous shifting of the ground for war (from self-defence against terrorists to the threat of WMD to humanitarianism, regime change and, with Obama, just war) has revealed a hegemonic power intent on war at all costs but uninterested in its legality or legitimacy despite the cosmopolitan rhetoric. Military might and technological brilliance, the signs of brutal sovereignty, have fully returned but are proving impotent against low technology and strong ideology.

2. The promise that market-led growth based on unregulated foreign investment and fiscal austerity would inexorably lead the global South to western economic standards has come to be seen as the greatest deception of our times. The gap between the North and the South, and between rich and poor, has never been greater. More than a billion people live on less than $1 a day. According to a 2006 UN report, average life in sub-Saharan Africa is less than half that in Northern Europe. Instead of equalising, globalised capitalism has led to the "bottom billion". The beginning of the end of neoliberal idolatry can be timed accurately: 15 September 2008 and the demise of Lehman Brothers. Greedy banks, conniving governments and economic "science", the witch medicine of our age, are still in mourning but reality has caught up with their convenient fantasies.

3. The former socialist countries moved fast from command economies to klepto-capitalism and from state oppression to market decadence without passing through a humane social and political order. The western panacea has been found inappropriate for many people at the heart of Europe.

4. Until recently, the western consensus was that torture takes place in exotic and evil places. This consensus has now dissolved. Torture returned to western camps and prisons, to Guatánamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, and has been extensively outsourced. It has become a respectable topic for "practical ethics" and jurisprudence conferences, where the "ticking bomb" hypothetical offers legitimacy and reveals the ugly underbelly of this new world order.

5. Old Europe, the willing minor partner in the cosmopolitan plans, has become seriously ill. Liberalism and social democracy, the proud social models it created, have atrophied as they converged towards the economics and politics of neoliberalism. The European Union has been emptied of political imagination and institutional will, as the sad shenanigans over the referendums and the Lisbon treaty attest. The current travails of Greece, Spain and Ireland are further evidence. The downgrading of Greece's credit rating by three unaccountable private companies which follow neoliberal orthodoxy is leading to externally imposed austerity, serious deterioration of living conditions and social unrest. These were the companies giving Lehman Brothers a top rating just before its collapse.

The response of governments to the end of neoliberal hegemony is still timid and uncertain. But people around the world have started reacting, as strikes in France, Greece and India, the Latin American popular movements and the reaction of youth to ecological catastrophe indicate. The great monotheistic religions have taught us that the messiah and the angel of history do not send a party invitation before arriving. Their lesson is invaluable. The return of history means that we can believe again in radical change even if we do not know when or how it will happen. The 21st century brings the age of western empires and cosmopolitanisms to closure.

The left is the main hope against an endgame of xenophobic, securitised, apocalyptic barbarism. But this is not the New Labour or German SPD nominal "left" nor that of departed "communism". New forms of socialism, new types of political subjectivity and solidarity are emerging in Latin America, in the ecological movement and in the ghettoes of our great cities. What the decade taught me was to expect radical change and to try to imagine a renewed socialism in which freedom cannot flourish without equality and equality does not exist without freedom. The new decade's resolution: one should become more radical as one grows older alongside the 21st century.

Text by Costas Douzinas

Friday 1 January 2010

Source : guardian.co.uk

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

The Dream Keeper

Bring me all of your dreams,

You dreamer,

Bring me all your

Heart melodies

That I may wrap them

In a blue cloud-cloth

Away from the too-rough fingers

Of the world.

Langston Hughes

You dreamer,

Bring me all your

Heart melodies

That I may wrap them

In a blue cloud-cloth

Away from the too-rough fingers

Of the world.

Langston Hughes

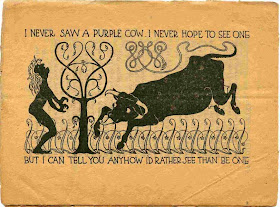

Victorian Nonsense

circa 1920.

This spectacular photograph shows what looks to be a rural farm home quietly

roaming across the prairie. The scene is incredibly tense as a single, lonely

tree stands in the background on the left, flanked by two additional (mobile?)

homes on the right. A smoky fog adds to the mystique of the photo. In another

lifetime, historians may come across this image and proclaim suburban sprawl

occurred in this manner: entire homes drifting quietly and blindly through a dusty,

undeveloped, (perhaps even war torn) landscape...

Source : mockitecture.blogspot.com

Modernologies

Contemporary Artists Researching

Modernity and Modernism

The newly established Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw strives to conduct profound research into the tradition of modernity. It acknowledges the burden of twentieth- century utopias imposed on Poland in its recent history, and finds critical readings of the project of modernity of particular relevance to its institutional mission.

Over the past three decades, critical work on the project of modernity and its related content has not only generated a broad range of activity in the academic field, but has also led to numerous works by artists researching modernity from their own perspective and with their own means. A younger generation of artists is again increasingly addressing the legacy of modernity and modernism and the failure of the utopia associated with these terms. What has prompted contemporary artists to investigate modernity and modernism, and its aesthetic manifestation? What are these artists' relationships to the promises and formal languages of modernity? How can this historical era even be critically reflected in and subjected to re-evaluation?

Modernologies sets out to explore artistic responses to modernity from its original reformist intention as a socio-political movement aspiring to cultivate a universal language. Diverging conceptions of modernity and the knowledge gained through postcolonial studies in recent years have led to the notion of 'multiple modernities'. Against this backdrop, this exhibition advocates neither a 'new formalism' nor a 'return to abstraction'. Nor is its aim to discover hitherto unknown or largely forgotten currents of modernism. On the contrary, the works on display fundamentally challenge the conditions, constraints and consequences of modernity. They expose ambivalences and attempt to develop new readings of the rhetoric of modernity and the concomitant grammar of modernism.

Modernologies unfolds a cartography of alternative viewpoints and narratives, lines of conflicts and unresolved contradictions. About 130 works and projects by more than thirty artists and collectives establish a new 'mapping of the critique of modernity'. The works featured in the exhibition are organised around three leitmotifs: 'the production of space', illustrated by a series of projects that explore the conflicts and correspondences between the architectural space of modernity and social and political space; 'the concept of a universal language', taking into account modernism's ideology and its attempt to create a universal language in the form of abstract aesthetic symbols and forms; and 'the politics of display', illustrating how artists use the exhibition itself as a medium, thus challenging the notion of display and playing the role of quasi-curators. The three sections of the exhibition not only intertwine, establishing countless dialogues, but also find a continuation in several works located outside these areas, or in transitional zones.

With works by Anna Artaker, Alice Creischer/Andreas Siekmann, Domènec, Katja Eydel, Ângela Ferreira, Andrea Fraser, Isa Genzken, Dan Graham and Robin Hurst, Tom Holert with Claudia Honecker, Marine Hugonnier, IRWIN, Runa Islam, Klub Zwei (Simone Bader and Jo Schmeiser), John Knight, Labor k3000 (Peter Spillmann / Michael Vögeli / Marion von Osten), Louise Lawler, David Maljkovic, Dorit Margreiter, Gordon Matta-Clark, Gustav Metzger, Christian Philipp Müller, Henrik Olesen, Paulina Olowska, Falke Pisano, Mathias Poledna, Florian Pumhösl, Martha Rosler, Armando Andrade Tudela, Marion von Osten, Stephen Willats, Christopher Williams, with many other artists in the film programme.

Curated by Sabine Breitwieser

Assistant curator: Magdalena Lipska

Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

ul. Pańska 3

00-124 Warsaw, Poland

12 February – 5 April, 2010

The exhibition was organized in collaboration with the Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA).

Modernity and Modernism

The newly established Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw strives to conduct profound research into the tradition of modernity. It acknowledges the burden of twentieth- century utopias imposed on Poland in its recent history, and finds critical readings of the project of modernity of particular relevance to its institutional mission.

Over the past three decades, critical work on the project of modernity and its related content has not only generated a broad range of activity in the academic field, but has also led to numerous works by artists researching modernity from their own perspective and with their own means. A younger generation of artists is again increasingly addressing the legacy of modernity and modernism and the failure of the utopia associated with these terms. What has prompted contemporary artists to investigate modernity and modernism, and its aesthetic manifestation? What are these artists' relationships to the promises and formal languages of modernity? How can this historical era even be critically reflected in and subjected to re-evaluation?

Modernologies sets out to explore artistic responses to modernity from its original reformist intention as a socio-political movement aspiring to cultivate a universal language. Diverging conceptions of modernity and the knowledge gained through postcolonial studies in recent years have led to the notion of 'multiple modernities'. Against this backdrop, this exhibition advocates neither a 'new formalism' nor a 'return to abstraction'. Nor is its aim to discover hitherto unknown or largely forgotten currents of modernism. On the contrary, the works on display fundamentally challenge the conditions, constraints and consequences of modernity. They expose ambivalences and attempt to develop new readings of the rhetoric of modernity and the concomitant grammar of modernism.

Modernologies unfolds a cartography of alternative viewpoints and narratives, lines of conflicts and unresolved contradictions. About 130 works and projects by more than thirty artists and collectives establish a new 'mapping of the critique of modernity'. The works featured in the exhibition are organised around three leitmotifs: 'the production of space', illustrated by a series of projects that explore the conflicts and correspondences between the architectural space of modernity and social and political space; 'the concept of a universal language', taking into account modernism's ideology and its attempt to create a universal language in the form of abstract aesthetic symbols and forms; and 'the politics of display', illustrating how artists use the exhibition itself as a medium, thus challenging the notion of display and playing the role of quasi-curators. The three sections of the exhibition not only intertwine, establishing countless dialogues, but also find a continuation in several works located outside these areas, or in transitional zones.

With works by Anna Artaker, Alice Creischer/Andreas Siekmann, Domènec, Katja Eydel, Ângela Ferreira, Andrea Fraser, Isa Genzken, Dan Graham and Robin Hurst, Tom Holert with Claudia Honecker, Marine Hugonnier, IRWIN, Runa Islam, Klub Zwei (Simone Bader and Jo Schmeiser), John Knight, Labor k3000 (Peter Spillmann / Michael Vögeli / Marion von Osten), Louise Lawler, David Maljkovic, Dorit Margreiter, Gordon Matta-Clark, Gustav Metzger, Christian Philipp Müller, Henrik Olesen, Paulina Olowska, Falke Pisano, Mathias Poledna, Florian Pumhösl, Martha Rosler, Armando Andrade Tudela, Marion von Osten, Stephen Willats, Christopher Williams, with many other artists in the film programme.

Curated by Sabine Breitwieser

Assistant curator: Magdalena Lipska

Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

ul. Pańska 3

00-124 Warsaw, Poland

12 February – 5 April, 2010

The exhibition was organized in collaboration with the Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA).

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Le Petit Journal des Refusees

In 1896, a rather short and obscure journal entitled Le Petit Journal des Refusees was published in San Francisco, California by a man named Gelett Burgess. Burgess, whose name was generally associated with humorous, satirical writing, teamed up with Porter Garnett, to produce this one-issued journal. Garnett, like Burgess, was classified as one of the Bohemian writers of San Francisco, was also the assistant curator of the Bankcroft Library from 1907-1912. Both men, well established, came together to produce this journal, of which little is known for sure, but much is supposed.

Burgess began his literary career in 1894 in San Francisco as associate editor of The Wave. While the cover of Les Petit Journal credits James Marrion 2nd as editor of the journal, Mr. Marrion did not in fact exist. Burgess did not sign his name to the journal, although hints to his identity are woven through the articles. Burgess, working by himself and not with Garnett, was also the editor of The Lark, whose publication overlapped with that of Le Petit Journal. The Lark was printed between1895-1897 and Burgess’s name can be clearly found on some covers and often within texts as well. He took open credit for The Lark while with Les Petit, he did not, using a pseudonym on the cover while alluding to himself and his work in other sections of the text. The Lark also contained an illustrated version of his famous poem “Purple Cow” in its first edition and while all three periodicals were considered radical departures from conventional magazines, it was The Lark that gained him considerable notoriety. Often associated with his non-sensical writing, his pattern of rhyme and his manuals for writing rhyme, including his Goop series, are considered children’s literary classics.

It is unclear why Burgess did not sign the one issue of Les Petit Journal that was produced. The journal seems to be dedicated to publishing the voices of ignored and ‘refused’ women, although the names of the women to whom the articles are accredited are barely known or again, unknown because they did not exist. Research shows that there was a real Nellie Hethington, although her married name was not Ford – it was Halbmaier – and her connection to Burgess could not be determined. There are no easily discernable traces of Alisse Rainbird or of Florence Lundberg either, for example. The Modern Journals Project (MJP) claims that all of the work in this journal seems to be that of one person, which would therefore substantiate the inability to identify these women as authors or writers of their time and further lead one to assume that Burgess (or Marrion, as the case may be) penned all of the articles in the journal.

At first glance, even before actually reading an entry, Le Petit Journal de Refusees provides many opportunities to intrigue and peak the interest of any reader. The many facets of the journal that pop out begin with the illustrations and the general shape of the journal itself. The use of whimsical art throughout and bordering every page, the variety in size and application of the font, even the use of outmoded wallpaper that has been cut trapezoidally, all diverge from the common printing practices of the time. Also quite remarkable is the nonsensical writing, both as actual pieces of literature and within the illustrations, deviate from the highly academic and often lofty writing that was being published in small journals of the time.

In comparing the art and illustrations of both Les Petit Journal and The Lark, there are definite stylistic similarities that would also lead one to believe that Burgess was also Marrion. The font styles are similar and so are the curviness of the lines and the feeling of each illustration. Without being an art historian or a curator, a simple study of both illustrations could allow one to deduce that they were both drawn and written by the same hand.

Dada was a cultural movement of artists and writers that looked to ridicule contemporary culture and traditional art forms. It was a reaction toward a morally corrupt society that was capable of creating WWI. It was a nihilistic movement that primarily involved the visual arts, literature, theater, and graphic design. The movement produced art objects in unconventional forms that were produced by unconventional methods.

Likewise, Surrealism sought to create the element of surprise through unexpected juxtapositions and the use of non-sequitor. This was accomplished through the use of conversational and literary devices that were absurd to the point of being humorous and confusing. The goal of Surrealism was to transform human experience by freeing people from the restrictive customs and structures of society.

The poem “Spring” is one of the many examples of how Burgess’s work plays with the ideas of Dada and Surrealism. While the subject of the poem is traditional, the execution of the subject matter is not. The lines do not follow a conventional pattern or form. In fact, the poem looks as if it is being edited in print. In this, Burgess implements typographical freedom. He chooses not to prescribe to traditional formatting. The irony in the illustrations perhaps lies in that while the poem speaks lyrically of green fields, buttercups, and cows, the illustration of alley cats climbing around crowded buildings in an urban setting is hinted at in the background.

Another example in the publication is “Our Clubbing List – refused by The Complete Alphabet of Freaks.” In this section, Burgess takes a very traditional practice used to help children learn the alphabet, and creates a very humorous, and at times scathing, list. He makes reference to fellow writers, artists, and publishers, sometimes in a complementary way, “B is for [Aubrey] Beardsley, this idol supreme. Whose drawings are not half so bad as they, seem”. Others are more scathing, “I am an Idiot, awful result of reading the rot of the Yellow Book cult” and “O is for Oblivion – ultimate fate Of most magazines, published of late”.

The illustrations on these four pages vary from page to page but all have a theme of interconnectedness. The first page of “The Clubbing List” features Burgess’s ‘Goops’ which were to become his trademark illustration.

As can be seen from these two examples, Burgess’s ventures into nonsense verse and cartoonesque illustrations were an attempt to refute literary realism through the affirmation of imaginative absurdity. In another twenty years, this would become the goal of Dadaism and then Surrealism as modernist movement.

Publisher and Editor: James Marrion, psuedonym for Gelett Burgess. Published: Ran for only one issue, Summer 1896. Published in San Fransisco, CA

Text by Cecilia G. Robles and Miriam L.Wallach

Modernist Magazines and Digital Humanities.

Source : www.macaulay.cuny.edu

Some Notes On the Experimental Marxist Exhibition

In the emerging canon of modern exhibition history, the Soviet contribution is usually represented by a sequence of elegant and innovative installations designed by El Lissitsky. In the Proun Room (Berlin, 1923) all six walls of the museum’s cube are activated to create “a way station between painting and architecture.” In the "Abstract Cabinet" (Hanover and Dresden1927-8) the viewer’s experience of the paintings on display is expanded three-fold by a wall of louvers that flicker from black to gray to white as the viewer walks past. And in the Pressa installation (the Soviet pavilion at the International Exhibition of Newspaper and Book Publishing in Cologne, 1928), a mural sized photomontage creates visual dynamism through the juxtaposition of the various camera angles and positions.1

But early Soviet museum policy was more diverse than Lissitsky’s transformative modernism, which in any case was more effective as an export commodity than a model for domestic consumption in the world’s first socialist society. During the 1920s, when cultural pluralism was still possible in the Soviet Union, one of the most successful alternatives to the avant-garde’s expanded white cube was the “museum of daily life” (bytovoi muzei), which placed works of art “in the setting that is most natural to them and most suited to their display”2 —religious art would be kept in the monastery-museum, the culture of the aristocracy in the palace-museum, and so on. (If this ideal of art preserved in its natural habitat smacks of Colonial Williamsburg, it also encompasses such terrains as Sir John Soane’s Museum and the Sigmund Freud Museum in London, both uniquely preserved archaeological sites.)

The brief extract from A. Fedorov-Davydov’s The Soviet Art Museum (1933) published here describes yet another alternative, the “experimental Marxist exhibition” that briefly dominated Soviet museum policy between 1929 and 1932. A largely forced response to the demand for a more politically literate population that accompanied the massive industrialization of the First Five Year Plan, the Marxist museum was designed to be in every respect the dialectical opposite of the bourgeois West’s “temple of art.” If capitalism maintained the status quo by preserving a strict hierarchy of the arts, proclaiming the cult of universal beauty, fetishizing the object, and equating aesthetic worth with market value, the Marxist museum must do the opposite. To reveal the social, economic, and political realities hidden beneath the myth of art’s universality, confrontations must be engineered, tensions unmasked, and artificial barriers removed. The history of art as a series of great individuals (“dead white men”) must give way to the history of art as a reflection of class struggle. The science of Marxist display must reveal, not self-sufficient and static objects, but the dynamic social processes of which they were part.

Fig. 1 - "French Art from the Era of the Decline of Feudalism and the Bourgeois Revolution." Installation at the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, 1931

What makes the Marxist exhibition of particular interest to museum history—and to contemporary art practice—is not its “vulgar socialism” (it was very soon rejected in favor of less strident and more conventional models) but its recognition of context and relationships as the principle source of meaning in the museum. Lissitsky’s attempts to activate the viewer by expanding and transforming the space of the gallery worked on the level of individual sensory experience. The Marxist installation was designed to fill that space with a pervasive awareness of the sociological conflicts underlying all art history, combining diverse artifacts—from “high” to “low” culture—to reveal relationships otherwise hidden. To function effectively, it had to take the form of an ensemble (kompleks), a carefully engineered environment in which painting, decorative art, mass media, text, photography, and architecture came together in a synthetic portrait of a particular class.

A strong resemblance can easily be seen between these early experiments and the work of a number of late 20th-century installation artists. Two examples come to mind. The first relates to the Hermitage Museum’s 1931 exhibition “French Art from the Era of the Decline of Feudalism and the Bourgeois Revolution.” [fig. 1] At the entrance to the exhibition the curator situates the viewer between the social extremes of the late Middle Ages. A mural-sized peasant tilling the soil (enlarged from a manuscript in the Department of Rare Books) is pitted against a mounted knight in full armor (from the Department of Weapons and Armor). Didactic wall texts—a major innovation of the new departments of political education—push home the broad ideological message implicit in the images.

Hans Haacke’s "Oelgemaelde. Hommage à Marcel Broodthaers," first shown at Documenta 7 in 1982, mobilizes space to very similar ends. Confronting each other across the gallery are a small oil portrait of Ronald Reagan and a gigantic photo mural of a peace demonstration in Germany, protesting the President’s lobbying for deployment of American missiles on German soil. The simple dialectic of might against right, of war and peace, is twice invoked: through the battleground layout of the images and through the choice of medium—for Reagan the oil painting, symbol of privilege, for the nameless crowd photography, which early Soviet culture had earmarked as the medium of the common man.

Fig. 2 - "Art of the Court Aristocracy in the Mid-Eighteenth Century." Installation at the State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow, 1930.

A second example turns on the way in which the materials of art provide a vehicle for unmasking the ideological position of a repressive ruling elite. The experimental exhibition “Art of the Court Aristocracy in the Mid-Eighteenth Century," shown at Moscow’s State Tretiakov Gallery in 1930, was a meager sampling of those artifacts that exemplified the class profile of the nobility. The shabby and makeshift result, the lack of dignity with which the assorted paintings, porcelain figurines, clocks, and cabriolet tables are treated, as if they are lots at an auction or the flotsam and jetsam of a second-hand store, is extraordinarily effective in destroying any latent glamour they might possess for the viewer.

The same strategy is used in reverse in the too-literal obedience to the conventional museum’s classification systems that Fred Wilson practiced in his “Mining the Museum” re-installation at the Maryland Historical Society in 1992. The jarring presence of a slave’s shackle in a display case of silver vessels, under the pretext that all are classified by the museum as metalwork, is a device that the new generation of Marxist museum educator would have understood and approved. In Fedorov-Davydov’s words, “Peasant painting does not cease to be painting just because it decorates the base of distaffs rather than pictures.”

With its combative, dialectic, revisionist, and leveling strategies for unmasking the true nature of reality and art’s sociologically determined meanings, the experimental Marxist exhibition can be seen as the prototype for one of the dominant forms of post-modernist art—the ideologically engaged installation in which individual objects are always subservient to the ensemble they create. Whether the truth to be revealed involves issues of class, race, gender, or sexuality, the position of the artist-curator-designer is that of social reformer and educator. It is not coincidental that the profession of the museum educator, interpreting and explaining the social history of art for the public, should have been pioneered in the Soviet Union as an integral part of the Marxist museum. Young museum professionals of Fedorov-Davydov’s generation drew a clear line between the curators of the permanent collection—almost all “bourgeois intellectuals” trained under the Old Regime—and the new, ideologically savvy educators, with their wall labels, gallery tours, mixing of high and low culture, and general disrespect for the aesthetic values of the traditional museum.

Fig. 3 - "Art of the Industrial Bougeoisie." Installation at the State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow, 1931.

Still, such comparisons with contemporary artists in the West are facile and misleading in one crucial respect. The Marxist method of museum display—and its intrinsic message of ideological struggle—must have a very different meaning for the viewer, depending on whether he lives in a capitalist or a socialist society. In “Avant Garde and Kitsch,” written in 1937 before the mystique of the Soviet Union had been entirely compromised by Stalinism, Clement Greenberg evoked the grass-is-greener yearning of the radicalized American intellectual trapped in the nightmare of capitalism and alienated from a proletariat that confused art with kitsch. The discontents of the avant-garde artist living under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat were more fundamental and less academic. In “Art of the Industrial Bourgeoisie,” an exhibition curated by Fedorov-Davydov for the Tretiakov Gallery in 1932, the museum functioned as a wall of shame or pillory where contemporary artists were held up to public ridicule and censure. On one wall examples of Suprematism and Abstraction are corralled by strips of quasi-Constructivist text that read “Bourgeois art in a blind alley of formalism and self-negation” (fig. 3) The similarity of this display to those of the Nazi regime’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition of 1937 shows better than anything else the perils of the experimental Marxist exhibition.

Problematic in a different way is the application of the Marxist exhibition’s gimmicks without any of its convictions or sense of purpose. The need to reveal a higher truth or unmask a bankrupt one has been the motivating factor behind sociology’s domination of aesthetics in much twentieth-century art. With no “greater good” to serve, the exhibition that reduces works of art to mere social manifestations exposes itself to the sort of scathing criticism that greeted the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s "Made in California" exhibition in 2000. “Think of the giant flea market at the Rose Bowl, albeit sifted and sorted and endowed with pretensions,” Christopher Knight wrote of the LACMA show. “It classifies diverse and unrelated materials according to common subject matter, regardless of artistic content. Instead of dogs or food, the subject matter here is ‘California’s image’ as seen in art.” 3

This is precisely the extremism that Fedorov-Davydov cautioned his colleagues against as they dismantled the old bourgeois temples of art. “An ensemble for its own sake, the simple mechanical combination in one place of all the branches of art without dividing them into primary and secondary, turns the museum’s galleries into an antique shop,” he writes in The Soviet Art Museum. Intended or not, the zeal with which shows like "Made in California" expand art’s cultural context at the expense of the art itself recalls those early experimental displays at the Tretiakov Gallery when exposing the universal class struggle was the only game in town. Such an irony would not have been lost on the political education departments of the Tretiakov or the Hermitage. The inability to distinguish avant garde art from kitsch could legitimately be seen as the ultimate fate of bourgeois society under late capitalism.

Text by Wendy Salmond

1. This sequence is paraphrased from Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October, 30 (1984), pp. 82-119.

2. Boris Shaposhnikov, “The Museum as a Work of Art,” Experiment, 3(1997), p. 233.

3. Christopher Knight, “Thematically Overwrought ‘Made in California’,” Los Angeles Times, 23 October 2000.

Wendy Salmond is Associate Professor of Art History at Chapman University in Orange, California. She is currently writing on the transformation of the Russian icon from cult object to work of art in the 1920s.

Source: X-Tra, Volume 5, Issue 1

But early Soviet museum policy was more diverse than Lissitsky’s transformative modernism, which in any case was more effective as an export commodity than a model for domestic consumption in the world’s first socialist society. During the 1920s, when cultural pluralism was still possible in the Soviet Union, one of the most successful alternatives to the avant-garde’s expanded white cube was the “museum of daily life” (bytovoi muzei), which placed works of art “in the setting that is most natural to them and most suited to their display”2 —religious art would be kept in the monastery-museum, the culture of the aristocracy in the palace-museum, and so on. (If this ideal of art preserved in its natural habitat smacks of Colonial Williamsburg, it also encompasses such terrains as Sir John Soane’s Museum and the Sigmund Freud Museum in London, both uniquely preserved archaeological sites.)

The brief extract from A. Fedorov-Davydov’s The Soviet Art Museum (1933) published here describes yet another alternative, the “experimental Marxist exhibition” that briefly dominated Soviet museum policy between 1929 and 1932. A largely forced response to the demand for a more politically literate population that accompanied the massive industrialization of the First Five Year Plan, the Marxist museum was designed to be in every respect the dialectical opposite of the bourgeois West’s “temple of art.” If capitalism maintained the status quo by preserving a strict hierarchy of the arts, proclaiming the cult of universal beauty, fetishizing the object, and equating aesthetic worth with market value, the Marxist museum must do the opposite. To reveal the social, economic, and political realities hidden beneath the myth of art’s universality, confrontations must be engineered, tensions unmasked, and artificial barriers removed. The history of art as a series of great individuals (“dead white men”) must give way to the history of art as a reflection of class struggle. The science of Marxist display must reveal, not self-sufficient and static objects, but the dynamic social processes of which they were part.

Fig. 1 - "French Art from the Era of the Decline of Feudalism and the Bourgeois Revolution." Installation at the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, 1931

What makes the Marxist exhibition of particular interest to museum history—and to contemporary art practice—is not its “vulgar socialism” (it was very soon rejected in favor of less strident and more conventional models) but its recognition of context and relationships as the principle source of meaning in the museum. Lissitsky’s attempts to activate the viewer by expanding and transforming the space of the gallery worked on the level of individual sensory experience. The Marxist installation was designed to fill that space with a pervasive awareness of the sociological conflicts underlying all art history, combining diverse artifacts—from “high” to “low” culture—to reveal relationships otherwise hidden. To function effectively, it had to take the form of an ensemble (kompleks), a carefully engineered environment in which painting, decorative art, mass media, text, photography, and architecture came together in a synthetic portrait of a particular class.

A strong resemblance can easily be seen between these early experiments and the work of a number of late 20th-century installation artists. Two examples come to mind. The first relates to the Hermitage Museum’s 1931 exhibition “French Art from the Era of the Decline of Feudalism and the Bourgeois Revolution.” [fig. 1] At the entrance to the exhibition the curator situates the viewer between the social extremes of the late Middle Ages. A mural-sized peasant tilling the soil (enlarged from a manuscript in the Department of Rare Books) is pitted against a mounted knight in full armor (from the Department of Weapons and Armor). Didactic wall texts—a major innovation of the new departments of political education—push home the broad ideological message implicit in the images.

Hans Haacke’s "Oelgemaelde. Hommage à Marcel Broodthaers," first shown at Documenta 7 in 1982, mobilizes space to very similar ends. Confronting each other across the gallery are a small oil portrait of Ronald Reagan and a gigantic photo mural of a peace demonstration in Germany, protesting the President’s lobbying for deployment of American missiles on German soil. The simple dialectic of might against right, of war and peace, is twice invoked: through the battleground layout of the images and through the choice of medium—for Reagan the oil painting, symbol of privilege, for the nameless crowd photography, which early Soviet culture had earmarked as the medium of the common man.

Fig. 2 - "Art of the Court Aristocracy in the Mid-Eighteenth Century." Installation at the State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow, 1930.

A second example turns on the way in which the materials of art provide a vehicle for unmasking the ideological position of a repressive ruling elite. The experimental exhibition “Art of the Court Aristocracy in the Mid-Eighteenth Century," shown at Moscow’s State Tretiakov Gallery in 1930, was a meager sampling of those artifacts that exemplified the class profile of the nobility. The shabby and makeshift result, the lack of dignity with which the assorted paintings, porcelain figurines, clocks, and cabriolet tables are treated, as if they are lots at an auction or the flotsam and jetsam of a second-hand store, is extraordinarily effective in destroying any latent glamour they might possess for the viewer.

The same strategy is used in reverse in the too-literal obedience to the conventional museum’s classification systems that Fred Wilson practiced in his “Mining the Museum” re-installation at the Maryland Historical Society in 1992. The jarring presence of a slave’s shackle in a display case of silver vessels, under the pretext that all are classified by the museum as metalwork, is a device that the new generation of Marxist museum educator would have understood and approved. In Fedorov-Davydov’s words, “Peasant painting does not cease to be painting just because it decorates the base of distaffs rather than pictures.”

With its combative, dialectic, revisionist, and leveling strategies for unmasking the true nature of reality and art’s sociologically determined meanings, the experimental Marxist exhibition can be seen as the prototype for one of the dominant forms of post-modernist art—the ideologically engaged installation in which individual objects are always subservient to the ensemble they create. Whether the truth to be revealed involves issues of class, race, gender, or sexuality, the position of the artist-curator-designer is that of social reformer and educator. It is not coincidental that the profession of the museum educator, interpreting and explaining the social history of art for the public, should have been pioneered in the Soviet Union as an integral part of the Marxist museum. Young museum professionals of Fedorov-Davydov’s generation drew a clear line between the curators of the permanent collection—almost all “bourgeois intellectuals” trained under the Old Regime—and the new, ideologically savvy educators, with their wall labels, gallery tours, mixing of high and low culture, and general disrespect for the aesthetic values of the traditional museum.

Fig. 3 - "Art of the Industrial Bougeoisie." Installation at the State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow, 1931.

Still, such comparisons with contemporary artists in the West are facile and misleading in one crucial respect. The Marxist method of museum display—and its intrinsic message of ideological struggle—must have a very different meaning for the viewer, depending on whether he lives in a capitalist or a socialist society. In “Avant Garde and Kitsch,” written in 1937 before the mystique of the Soviet Union had been entirely compromised by Stalinism, Clement Greenberg evoked the grass-is-greener yearning of the radicalized American intellectual trapped in the nightmare of capitalism and alienated from a proletariat that confused art with kitsch. The discontents of the avant-garde artist living under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat were more fundamental and less academic. In “Art of the Industrial Bourgeoisie,” an exhibition curated by Fedorov-Davydov for the Tretiakov Gallery in 1932, the museum functioned as a wall of shame or pillory where contemporary artists were held up to public ridicule and censure. On one wall examples of Suprematism and Abstraction are corralled by strips of quasi-Constructivist text that read “Bourgeois art in a blind alley of formalism and self-negation” (fig. 3) The similarity of this display to those of the Nazi regime’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition of 1937 shows better than anything else the perils of the experimental Marxist exhibition.

Problematic in a different way is the application of the Marxist exhibition’s gimmicks without any of its convictions or sense of purpose. The need to reveal a higher truth or unmask a bankrupt one has been the motivating factor behind sociology’s domination of aesthetics in much twentieth-century art. With no “greater good” to serve, the exhibition that reduces works of art to mere social manifestations exposes itself to the sort of scathing criticism that greeted the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s "Made in California" exhibition in 2000. “Think of the giant flea market at the Rose Bowl, albeit sifted and sorted and endowed with pretensions,” Christopher Knight wrote of the LACMA show. “It classifies diverse and unrelated materials according to common subject matter, regardless of artistic content. Instead of dogs or food, the subject matter here is ‘California’s image’ as seen in art.” 3

This is precisely the extremism that Fedorov-Davydov cautioned his colleagues against as they dismantled the old bourgeois temples of art. “An ensemble for its own sake, the simple mechanical combination in one place of all the branches of art without dividing them into primary and secondary, turns the museum’s galleries into an antique shop,” he writes in The Soviet Art Museum. Intended or not, the zeal with which shows like "Made in California" expand art’s cultural context at the expense of the art itself recalls those early experimental displays at the Tretiakov Gallery when exposing the universal class struggle was the only game in town. Such an irony would not have been lost on the political education departments of the Tretiakov or the Hermitage. The inability to distinguish avant garde art from kitsch could legitimately be seen as the ultimate fate of bourgeois society under late capitalism.

Text by Wendy Salmond

1. This sequence is paraphrased from Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October, 30 (1984), pp. 82-119.

2. Boris Shaposhnikov, “The Museum as a Work of Art,” Experiment, 3(1997), p. 233.

3. Christopher Knight, “Thematically Overwrought ‘Made in California’,” Los Angeles Times, 23 October 2000.

Wendy Salmond is Associate Professor of Art History at Chapman University in Orange, California. She is currently writing on the transformation of the Russian icon from cult object to work of art in the 1920s.

Source: X-Tra, Volume 5, Issue 1

Monday, February 1, 2010

Astro Boy

I feel compelled to write about a horrific poster i saw today of an American film ‘Astro Boy’ based on the manga/anime of the same name. It’s happening a lot recently, with unnecessary and mostly offensive remakes (even the karate kid, inexplicably set in China), but I was particularly upset with Astro Boy because of its completely gratuitous westernisation.

Obviously Astro Boy was always a commercial product. In true Japanese fashion, a huge amount of money has been squeezed out of the series in terms of manga, anime series, film, merchandise, games, sponsorship etc., so its not that I’m whinging about the studios just trying to net cash; its the apparent need to take original (and more importantly commercially proved) ideas, and conform them to western/hollywood standards. What will kids delight in by seeing yet another ubiquitous pixar-style 3D feature with the same plot again?

I’m currently watching Dennou Coil, a recent anime series which is the current inspiration for a lot of AR industry projects. It reminded me of the quiet, bittersweet character of a lot of Japanese childrens tv/fiction and how unexpectedly fresh and touching the character development and storytelling is. Children don’t seem to care that much about cultural boundaries either; Disney is huge in Japan, and Japanese anime is big all around the world. Astro Boy was a lot of fun, but touched on a lot of issues (death, rejection, obsession, war) that are maybe considered too adult for the kids of today. I think they can handle it though, and in the right hands Astro Boy would be a great vehicle to present some new storytelling methods and visual styles to the mainstream feature format. The original manga was a big smash in the US too, so the move to ‘update’ the visuals and dumb down the storyline seem ill-motivated. As it is, I feel slightly robbed.

Keiichi Matsuda

Source :Keiichi Matsuda blog, January 18, 2010.